Projects

Student Power on the Prairie: UNL in the SixtiesProject Editor: Alex Stamm, History 470: Digital History, Spring 2008

Introduction

The collective memory of Vietnam War-era demonstrations generally thinks of mass student protests at places like Berkeley, Columbia, and other elite or coastal schools and cities. Only a couple instances of protest in the Midwest remain familiar, including the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago or the 1970 shootings of four students at Kent State in Ohio.

Chicago and Kent State were only the most well-known Midwest events during the Sixties. But struggles against racism, protests against the Vietnam War and the draft, the fight for student power, among other issues, occurred throughout the Midwest. At the University of Nebraska, major political issues were raised concerning the free speech of students, student control of the university, the collusion of Lincoln businesses with racism and apartheid, and ultimately the Vietnam War.

Prelude

Throughout the 1950s, the Red Scare in America hunted communists throughout the country, real or imagined. Much of the persecution was carried out by a House of Representatives Committee called the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC. [1] By 1961, much of the paranoia and hyperbole had passed, leaving much of the American "Old Left" and even many non-Leftists devastated. Red-baiting and charges of communism persisted through the Sixties, however, including Nebraska. That winter the UNL student newspaper, The Daily Nebraskan, ran an article about an essay contest from the New World Review, "a communist monthly publication." A former state senator from Fremont, Ray Simmons, would later point to the essay contest article as proof of the paper promoting communism. The controversial essay topic in question was, "Nuclear warfare threatens the future of all young people." [2] Simmons pointed further at two Daily Nebraskan editorials criticizing the HUAC. [3] Simmons called on the Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, Clifford Hardin, to take action against the Daily Nebraskan, arguing "the time is long overdue for the chancellor of the university to tell us what he intends to do to stop this sort of thing." [4]

Little came of Simmons' efforts. Chancellor Hardin remained committed to defending the free speech of the Daily Nebraskan. [5] The Regents of the University of Nebraska, as well, took no action. However, Simmons did succeed in a couple of areas. First, he received the backing of some Nebraska businessmen, garnering the endorsement of the Junior Chamber of Commerce (the "Jaycees") in his endeavor. [6] Second, the issue garnered a significant amount of local press and attention, including the Norfolk Daily News, the Nebraska City Press, the Grand Island Independent, the Lincoln Star, the World Herald, the York Times, the Alliance Daily and especially the Fremont Tribune. The reaction from Nebraskans ranged from defending the free speech of students to paternalistic criticism of the naivete of the students.

The issue died down for nearly two years, but Simmons' criticism of the Daily Nebraskan would arise once again in 1963. In March of that year, Simmons compiled article clippings from the Daily Nebraskan to prove it was promoting liberalism and discrediting conservatism. Simmons once again called on the University of Nebraska Regents to investigate the paper. [7] Both the editor of the Daily Nebraskan, Linda Jensen, and the director of the School of Journalism (or "J-School"), William Hall, responded quickly. Jensen said Simmons was "carrying on a personal anti-liberal campaign to the detriment of the entire state," while Hall accused Simmons of using selective and unrepresentative examples in the clippings. The Daily Nebraskan staff provided 40 article clippings with a conservative viewpoint, backing up Hall's point. [8] Again the charges received wide coverage from numerous local newspapers for a couple of weeks. However the result was generally the same. Some responses included paternalism, many argued the Daily Nebraskan had freedom of speech and press. Ultimately, the Board of Regents refused to investigate the Daily Nebraskan. [9]

The minor Red Scares at the University of Nebraska at this time tested the resolve of the

administration to protect free speech and freedom of the press. It was also an early victory

for student rights. Both student rights and free speech would become even more important, locally and nationwide, in the years ahead.

SDS Comes to Campus

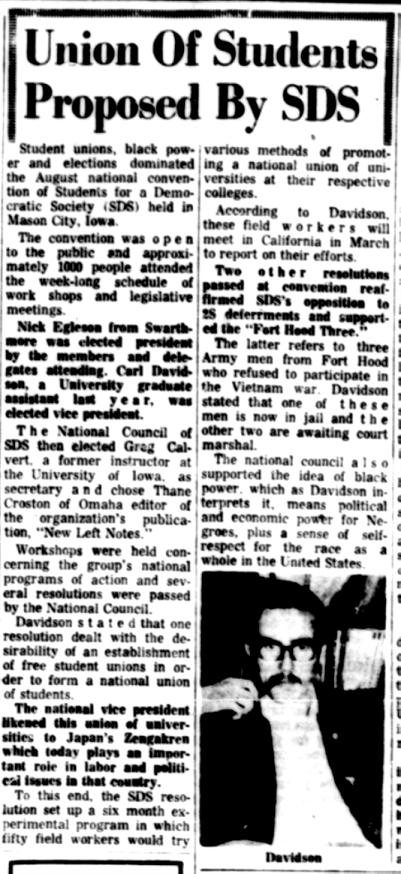

Originally from Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, Carl Davidson had joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) while an undergraduate at Penn State. In 1965, Davidson became a graduate student of philosophy at the University of Nebraska. Viewing Nebraska as "virgin territory" for SDS activism, he and another student created a new chapter within days of arriving. They immediately set out building the chapter and planning their first events. [10]

Students for a Democratic Society had emerged from an "Old Left"organization, the League for Industrial Society. Due to conflicts over the exclusion or inclusion of communists and the freedom of the new group to act independently, SDS and LID split. SDS became the leading organization of a "New Left," which was less labor-oriented, not interested in either communism or anti-communism, and more focused on youth, anti-racism, and cultural alienation. Later, the New Left would, during and after the break-up of SDS in the late Sixties, provide early ground for the emergence of feminism, gay rights, and more anti-racism movements.

In October, Carl Davidson and others held a Vietnam Teach-In in Love Library to educate people about the war. The Teach-In, one of many that SDS held across the country, was a huge success, drawing in a large number of students and a great deal of press. Dr. David Trask, an assistant professor of history at the University, discussed the history of American involvement in Vietnam. Other aspects of the war were discussed, and SDS made sure to include pro-war speakers. [11]

The Vietnam Teach-In was the first event on campus about the Vietnam War since the Student Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy had demonstrated in front of the Military and Naval Science building the semester before. [12] Like the SANE demonstration, the Teach-In garnered press and letters to the editor with much the same arguments.

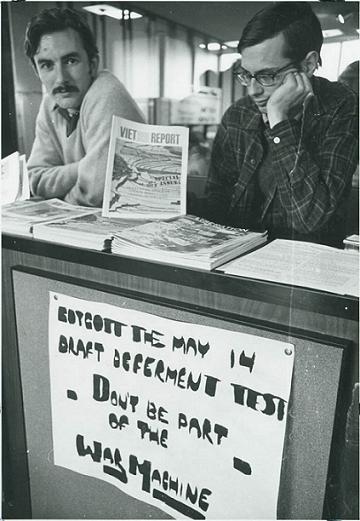

Then, SDS suffered some trouble. Coming off of the April 1965 March on Washington and the successful nationwide Teach-Ins, SDS had to deal with how to respond to the draft. The matter was put to a vote by all chapters. The vote was in favor of calling for a nationwide program of draft resistance and educating potential draftees on how they could legally avoid the draft. UNL's chapter, however, did not vote. Not having been recognized by a national convention of SDS, held annually, the chapter was not polled. SDS's position on the draft caused the UNL chapter's vice president, Larry Clawson, to resign in protest. [13] Days later, UNL's chapter voted unanimously to support the draft resistance program and distribute a War Resisters League pamphlet telling people to apply for conscientious objector status called "G.I. or C.O.?" [14] Especially after student draft deferments were revoked, by what the Daily Nebraskan called the "Nebraska not-too Selective Service," draft resistance would continue to be an issue on campus throughout the Vietnam War. [15]

Carl Davidson had a talent for organizing, and proved it during the spring semester of 1966. SDS

put together a week-long "South African program" featuring a teach-in on South Africa's system of

racial apartheid and a demonstration at downtown Lincoln corporations linked with apartheid by their investments. Participating in the teach-in was an extensive list of persons, including Davidson, English Professor Karl Shapiro, History Professor David Trask, Reverend Hudson Phillips, and a Rhodesian student named Gowdin Dubray. [16] The South African program culminated in the two-and-a-half mile downtown demonstration, which protested in front of five businesses for two hours. [17] The protest was led, Davidson says, by the University's star black football players. [18] The demonstration made SDS and Carl Davidson well-known locally.

Student Power!

Youth across the United States watched the events at the University of California Berkeley in 1964. That year Mario Savio and other students challenged in loco parentis rules and restrictions on student political organizing. The battles at Berkeley would rage for several years, but the events of that year proved instrumental and inspiring to many young students across the country.

In 1965, students at the University of Nebraska were expanding their own political freedom. Carl Davidson and Liz Aitken, after some wrangling with the administration, established a free speech forum called Hyde Park in the student union, held on Thursdays. [19] Hyde Park allowed anyone, right-wing, left-wing, centrist, even apolitical, people to speak on the microphone, usually with a limit of four minutes. Hyde Park became a staple of campus political discussion and often attracted a large crowd of listeners. Speakers such as UNL professors David Trask, Royce Knapp, and Dr. Marxer, countercultural icon Allen Ginsberg, student government candidates, and regular students spoke at Hyde Park over its years on campus.

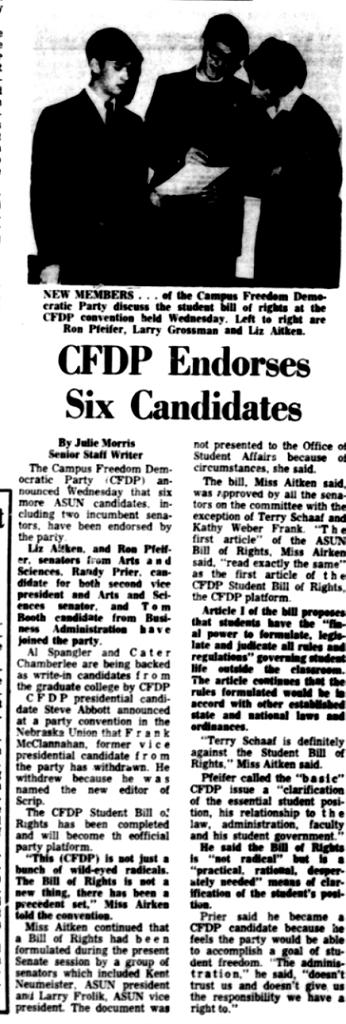

The campus chapter of SDS even launched a political party for student government. [20] Modeling itself on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a civil rights party formed in 1964, the Campus Freedom Democratic Party made student rights on campus a major campaign issue and attempted to get candidates elected to the student government, the Associated Students of the University of Nebraska (ASUN). The CFDP proposed as its platform a Student Bill of Rights. Larry Grossman, CFDP candidate for Arts and Sciences senator, said the basis of the Bill of Rights was that "students should have the final say over all things that govern them outside of the classroom." CFDP candidate for president, Steve Abbott, said that were such a bill passed by student government and vetoed by the dean of Student Affairs, the student government would stage a walkout and demand new elections to show the students supported the bill. [21]

The Campus Freedom Democratic Party popularized the issue of student rights on campus, even forcing the main opposition party, Vox Populi, to put forward their own watered-down version of student rights. [22] Nevertheless CFDP managed to get only a handful of candidates elected, none of them to the executive positions. [23] However that did not mean the end of the issue. Steve Abbott continued to advocate for a Student Bill of Rights as a graduate student representative in student government, and the Fall 1966 editor of the Daily Nebraskan devoted a great deal of attention to student rights. [24]

During this time, Carl Davidson was collecting his ideas about student rights and student government. Drawing from the radical American labor tradition of the International Workers of the World and anarchist syndicalist ideas, Davidson wrote a series of essays which became famous within SDS nation-wide. The earliest of these, written while he was at UNL, was titled "Toward a Student Syndicalist Movement, or University Reform Revisited." The essay urged students to take one of two methods towards changing their schools, depending on how open their student government already was. One, they could form a Campus Freedom Democratic Party, as Davidson and others had done at UNL. Ideally the CFDP could push demands "in the form of a Bill of Rights or Declaration of Independence or both." If the demands were not met, Davidson said, the CFDP should "promptly abolish student government or set up a student-government-in-exile," followed by a variety of protest and civil disobedience. Or two, the students can form a Free Student Union. The FSU would serve as a parallel institution to the regular student government, encourage people not to participate in the student government, and eventually declare the student government defunct and make demands on the university administration. [25] The essay proved so popular that at the 1966 SDS National Convention in Clear Lakes, Iowa, he was urged to run for National vice president and won. Although he would come back to Lincoln occasionally, organizing for SDS nationally would take a great deal of Davidson's time from then on; he dropped out of grad school that summer and devoted himself to SDS. [26]

"DO Something About It!": The 1970 Student Strike

SDS would have some continuing influence over the next few years after Davidson and Steve Abbott left UNL. The CFDP changed its name soon after the two student activists left, not wanting to be associated with Davidson's radically syndicalist ideas, and continued promoting a Student Bill of Rights. [27] Draft resistance, which had been controversial when SDS first took the position, again became a major issue when Dr. Marxer, a professor of philosophy, attempted to form the Nebraska Draft Resistance Union in 1968. [28] The NDRU lasted only a short while. Calls for Marxer to be fired and charged with treason were made in letters to Chancellor Hardin and to the local newspapers. [29] The Board of Regents decided, rather than spark a free speech controversy by firing Marxer, to let his contract expire without renewal that summer. The University chapter of SDS saw many of its members put their energies towards the 1968 presidential campaign of the peace candidate, Eugene McCarthy, and the group became less active on campus. In 1969 ideological disagreements within the national organization became full blown, SDS split apart into competing factions and then dissolved.

The campus, however, became less apathetic and increasingly political despite the loss of SDS. A chapter of Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus group that had often opposed SDS (and on occasion worked with SDS) at universities across America, was established. The Vietnam Moratorium Committee formed a chapter on campus in the fall of 1969. ASUN President Steven Tiwald became heavily involved in the National Student Association, which had become increasingly against U.S. involvement in Indochina over the years. A variety of ad hoc political groups and coalitions would form over the next few years until the end of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

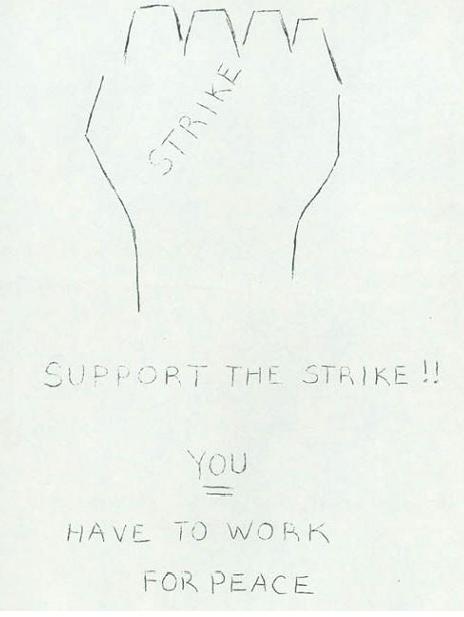

The biggest antiwar protests on campus happened, as they did at hundreds of other colleges across the nation, when President Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia on April 30, 1970. The Vietnam Moratorium Committee, working with ASUN and Steve Tiwald, immediately went into action to form a demonstration. [30] Fliers appeared with the question "Angry about what Nixon's doing in Cambodia? Be outside the union (north side) 1:30 Monday May 4 And DO Something About It!!!" [31] The rally took place in the plaza of the student union, where a Hyde Park-style open microphone was in use. Two students used the microphone to call for a march on the Draft Board office at the Terminal Building on 'O' Street, a short walk from campus. Many others followed, including Professor Stephen Rozman, who would be criticized for his actions during the student strike. Two police officers prevented an estimated 75 to 150 students from entering the 9th floor office. As more police arrived, the demonstrators were ordered to leave, and 13 were arrested (11 for failing to disperse, 1 for property damage, and 1 for obscene language). [32]

Nearly 200 students met that night on a campus ministry, along with a few members of the faculty, including Dr Rozman. This group made plans to occupy the ROTC building (the Military and Naval Sciences building), and around 100 promptly did so. Police had suspected the building would be a target for some kind of protest and had a few officers on the scene beforehand. However, these officers proved incapable of keeping the students out. The students had taken control of the building. University administrators immediately took action to remove the students, including an attempt to get a legal injunction on the protest in the middle of the night, with ultimately no effect. Within hours, the crowd of occupiers had swelled to 1,800. [33]

A group of students who had assumed the role of spokespeople for the demonstrators drew up a list of demands, which was later published in the Daily Nebraskan. These demands included amnesty for those arrested at the Draft Board; that the administration endorse the strike; that ROTC be suspended until the end of the war (this was amended from an earlier version calling for abolition of the ROTC); that campus police no longer carry guns on campus; that meetings of the Board of Regents be public; and that free University classes get one hour of credit towards degrees. [34] None of the demands were immediately accepted though some have become a reality in the years since, including the demand that Regents meetings be made public and campus police no longer carry guns.

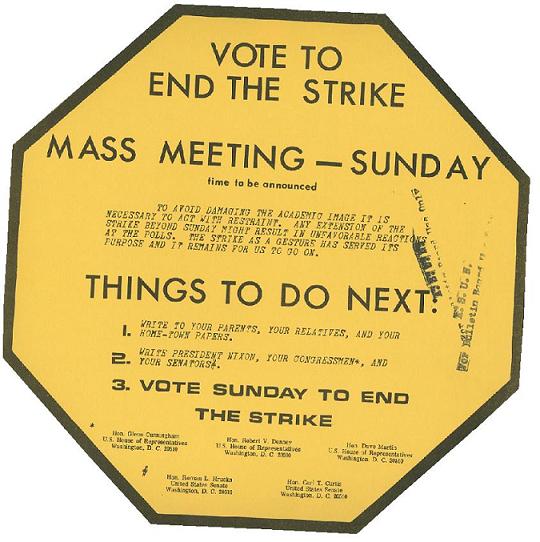

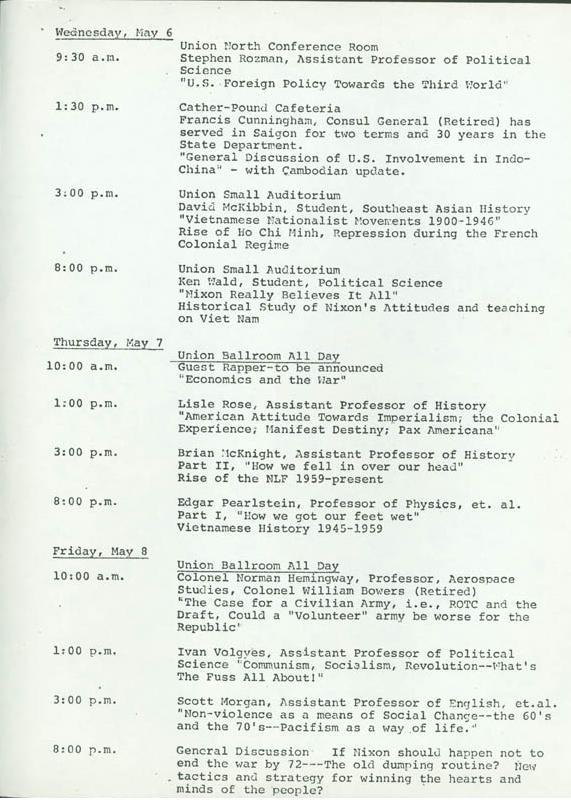

By 10 a.m. the next morning, after the numbers of occupiers had decreased to an estimated 200 and with the administration threatening suspension, the remaining students vacated the building to attend an ad hoc faculty meeting at the Student Union. [35] But the strike continued for the rest of the week. Rallies were held often including one for the victims of Kent State, where four students had been shot by the National Guard on May 4th, a town hall style meeting of students which attracted thousands on May 5 (a similar rally would be held for the 2 black victims at Jackson State on May 15), and another rally of thousands on May 9 was put together by students, Rural Nebraskans for Peace, and Nebraskans for Peace. The next day, at another town-hall style meeting, a vote was taken on whether or not to continue the strike. ASUN had set up a variety of events called the "Czechoslovakian Spring Festival" (likely a reference to the Prague Spring of 1968) to educate students about the war and its history. [36] Young Americans for Freedom had been actively urging faculty to oppose the strike. [37] At the same time an ad hoc group called the Committee for Undisrupted Education distributed yellow "stop sign"-shaped fliers calling on students to vote against continuing the strike. [38] CUE succeeded in its efforts, with the vote being 1,357 against the strike and 1,030 for the strike. [39]

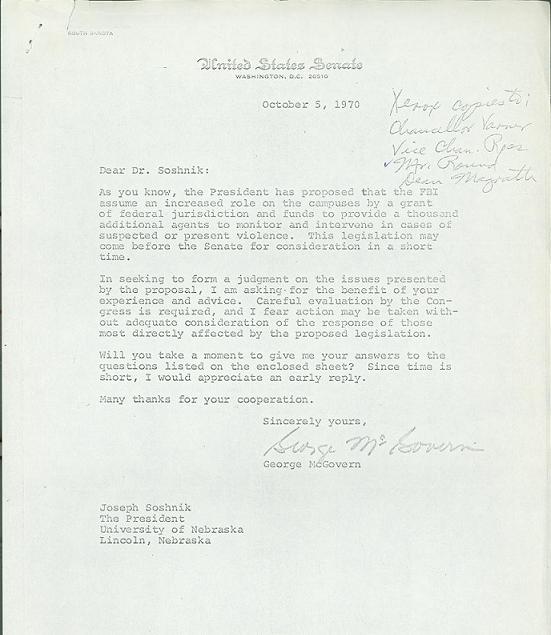

Little disciplinary action was taken. The Report of the Board of Regents on the "campus disruption" (which found little was actually disrupted, including classroom attendance) described the actions of university administrators, Dr. Rozman and other faculty aiding the student strikers, and the students themselves as "improper." [40] Despite not having a required constitution, the Vietnam Moratorium Committee had functioned as any other organization until a month after the strike, when the university no longer considered them to be a Recognized Student Organization. [41] Additional reports on the strike were created by the CUE in the fall. [42] In the wake of the campus demonstrations, occupations, and riots which had occurred, President Nixon introduced a plan for an increased role and presence of the FBI on campuses, which led South Dakota Senator George McGovern to send a letter and questionnaire to many university administrators, including UNL President Joseph Soshnik. [43] Little seems to have come from that effort and FBI surveillance and harassment of dissidents was, to some extent, curtailed following in the mid-Seventies.

Conclusion

What each of these stories shows is that, despite being a non-elite, open admissions, Midwestern

school, major aspects of the social change occurred on the UNL campus. Students for a Democratic

Society played a large role initially in introducing the idea of student rights and student power

to the university. Sympathetic editors of the student newspaper continued the process, and students themselves clearly favored some action on the issue. Groups like SDS and Friends of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (FSNCC) made civil rights, black power, and apartheid an issue not only on campus but for the larger Lincoln community. Certain professors, such as David Trask, Stephen Rozman, and others regularly encouraged students to organize and act. And like many colleges, students at UNL were outraged when Nixon, who had promised peace in Vietnam, went on to expand the war. The events of the Sixties occurred here, as they did across the Midwest and across the nation.

Works Cited1. Jules Boykoff, Beyond Bullets: The Suppression of Dissent in the United States. AKPress, May, 2007. 2. Fremont Tribune, "Simmons Hits U of N Paper for Contest," 7/11/1961. 3. Fremont Tribune, "Simmons Agrees to N.U. Talk," 7/12/1961. 4. Fremont Tribune, "Simmons Replies to Chancellor," 7/13/1961. 5. Fremont Tribune, "Simmons Replies to Chancellor," 7/13/1961. 6. Lincoln Star, 7/31/1961. 7. Nebraska City Press, 3/4/1963. 8. Lincoln Journal, "J-School Head Gives Simmons 'F' Grade on His Pamphlet," 3/3/1963. 9. Hastings Tribune, 3/21/1963. 10. Robbie Lieberman, Prairie Power: Voices of 1960s Midwestern Student Protest, pp. 33-34. University of Missouri Press, April, 2004. 11. Daily Nebraskan, "SDS Teach-In: Opposing Views Heard, Argued," 10/18/1965. 12. Daily Nebraskan, "SANE to Conduct Demonstration Today," 4/12/1965. 13. Daily Nebraskan, "SDS Statment [sic] Back, Anti-Draft Movement," 10/20/1965. 14. Daily Nebraskan, "SDS Favors Draft Protest," 10/22/1965. 15. Daily Nebraskan, "'A Real Break' Deferments To Be Revoked," 5/6/1966. 16. Daily Nebraskan, "SDS Teach-In To Climax South African Program," 3/14/1966. 17. Daily Nebraskan, "Businesses Pickets, Marchers Protest Apartheid," 3/21/1966. 18. Lieberman, p. 34. 19. Daily Nebraskan, "New Plan Includes 'Hyde Park' Forum," 9/29/1965. 20. Daily Nebraskan, "Political Party Unveiled," 4/1/1966. 21. Daily Nebraskan, "CFDP Proposes 'Bill of Rights' Platform," 4/7/1966. 22. Daily Nebraskan, "VP Has Bill of Rights," 4/21/1966. 23. Daily Nebraskan, "CFDP Stand Now," 4/29/1966. 24. Daily Nebraskan, "Abbott, CFDP Advocate Rights Enactment Plan," 9/16/1966. 25. Carl Davidson, New Radicals in the Multiversity And Other SDS Writings on Student Syndicalism, p. 47-49. Charles H. Kerr Publishers Company, December, 1990. 26. Lieberman, pp. 37-40. 27. Daily Nebraskan, "CFDP May Change Title," 10/20/1966. 28. Nebraska Draft Resistance Union, Press Conference, 3/21/1968. 29. A. Eileen Shearer, Letter to Chancellor Clifford Hardin, 3/21/1968. University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations. 30. "Report of Inquiry on Disruptive Actions on the University of Nebraska Campus, Lincoln-April 30-June 10, 1970," hereafter "Regents Report," 8/12/1970, pp. 1-2. 31. Unidentified author(s), ASUN-approved flier, 1970, from the University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations. 32. Regents Report, p. 2. 33. Regents Report, pp. 2-4. 34. Regents Report, p. 4. 35. Regents Report, p. 5 and p. 8. 36. Unidentified author(s), Fliers from Special Subject Files-Demonstrations, University of Nebraska Special Collections. 37. Michael Egger, David Paas, and Tom Siedell, "Outside The Tower" statements by the UNL chapter of Young Americans for Freedom to the UNL Student-Faculty Liaison, 1970. University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations. 38. Committee for Undisrupted Education, Flier, 1970. University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations. 39. Regents Report, pp. 10-11. 40. Regents Report, pp. 18-20. 41. Regents Report, p. 2. 42. Committee for Undisrupted Education, reports on the May 1970 student strike, Fall 1970, University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations. 43. George McGovern, letter to University of Nebraska President Joseph Soshnik, October 5, 1970. University of Nebraska Special Collections, Special Subject Files-Demonstrations.

|