Projects

The Rise and Demise of the Latin SchoolProject Editor: Kimberly Kraska, UCARE, 2007 Table of ContentsOverview

|

"To read the Latin & Greek authors in their original, is a sublime luxury . . . I thank on my knees, him who directed my early education, for having put into my possession this rich source of delight; and I would not exchange it for anything which I could then have acquired, & have not since acquired." -Thomas Jefferson to Dr. Joseph Priestley, Philadelphia, Jan. 27, 1800. From: Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

| Willa Cather as a 2nd year Prep, 1890-91 |

The Beginning

Since the chartering of the University of Nebraska in 1869, the Board of Regents wanted to ensure and increase the usefulness of the University. The Board of Regents decided to create a preparatory department for the University's welfare. The preparatory department or the Latin School, which was the name given to it soon after its establishment, came about due to the fact that secondary education in Nebraska was minimal in some areas and barely existent in other areas of Nebraska. Nebraska students, entering the University, were poorly prepared for the college curriculum. To turn the eager students from furthering their education would go against the concept of the University. In turn, if this happened, it would have jeopardized the integrity of the University as well as threatening its survival. However, letting anyone in is not any better. Certain scholastic expectations and standards must be followed as a prerequisite for entrance into the University.

No explicit provision in the University's charter called for the formation of this department or for its support. Following suit of other universities in the Midwest like University of Michigan, the Board of Regents took a chance. On June 13, 1871, at a Board of Regents meeting the new chancellor, Allen R. Benton implemented a plan for the course of study for the preparatory department, and was soon adopted.

Course of Study

The course of study focused on classical studies such as Latin, rhetoric, ancient history, algebra, geometry, and Greek, because knowledge of these subjects would build mental discipline and improve moral character. In addition to the classical focus, there was an inclusion of modern physical and social science studies in the curriculum so; physical geography and United States history were added. In 1872, two curriculum tracks appeared, the "Classical" and the "Scientific," which corresponded to the work in the Latin School with that of the University's curriculum.

Entrance Requirements

Entrance into the Latin School was open to any male or female, who had to be at least fourteen years old, exhibiting good moral character, and most importantly, be able to pass an entrance examination in reading, spelling, English grammar, practical arithmetic, and descriptive geography.

Instruction

The first classes for the preparatory department were held in September 1871, coinciding with the University's term. Instruction for the classes was given by tutors to professors. The head tutor was the Principal of the Latin School.

The first principal of the Latin School was George E. Church. He was principal from the opening of the department until 1875 when the Board of Regents promoted him to Professor of Latin Language and Literature. As principal of the Latin School, Church was the only non-cleric on the original faculty. In 1882, he left his twelve year teaching career at the University when he was fired by the Board of Regents. He continued on in Fresno, California to become a Judge on the Fresno Superior Court.

With the beginning of the department, the duties of the Principal were unclear and not outlined yet. Some of the tutors were mostly students, employed part-time; however, the inadequacy of their number bothered Chancellor Benton but his plea was unheeded. Nonetheless, due to the enrollment pressure the majority of the preparatory workload fell on the University professors and including the Chancellor, himself. The purpose of the Latin School was to provide instruction in the elementary branches as well as to unofficially prepare common school teachers. This multi-faceted philosophy for the Latin School would, later in decade, cause conflict.

However, the instructional tools were basically the skill of the instructor and a textbook. Allen and Grennough's Latin Grammar, Goodwin's Greek Grammar, Liddell's Rome, Olney's Algebra, and Gray's Elements of Botany were the textbooks used in for instruction. The methodology of instruction was lecture and rhetorical recitation.

Changes in Course of Study

Over the years, the course of study was adapted with the changes and needs of the University as well as the performance of the preparatory students. These changes can be seen in the Board of Regents minutes and papers as well as the Catalogues and Bulletins of the University. For example, in 1875, the Board of Regents extended the Scientific preparatory course to two years instead of the one initially established. With the changes in the course of study, Chancellor Benton felt that at times, the University was lowering the academic standards. Maintaining and improving the academic reputation of the University was important in the early history of the school. In addition to the reputation of the University, it also needed students to ensure its effectiveness and survival, the Latin School shared this paradox also.

Enrollment

Initially, the student enrollment in the Latin School was well over half of the total students enrolled in the University. The preparatory department supplied the University with its students. Enrollment hit its peak in 1880 when 71 percent of all University students were enrolled in the Latin School according to the Register and Catalogues of the University. This trend would not diminish until the mid-1880s. The average annual enrollment for the Latin School for the years 1872-1877 was 108 students. Despite the boost in enrollment, on average Chancellor Benton stated to the Board of Regents on June 25, 1873, that 20 students annually entered the University from the Latin School. A good portion of the students that enrolled into the Latin School did not have any ambition to continue on to the University proper. Only a handful of students would enter the University, with the rest undermining the purpose of the preparatory department.

Sub-Freshman

Since the Latin School was an extra legal creation of the Board of Regents, classification of the preparatory students became an issue concerning their relation to the University proper. Chancellor Benton and Regent McKenzie suggested to the Board of Regents in their report in December 1874, that the students in the preparatory department be classified as "sub-freshman" rather than Latin School students. The committee that Benton and McKenzie were on, also recommended that the Principal of the Latin School become apart of the University proper staff as Assistant Professor of Ancient and Modern Languages. This position would unify the preparatory department with the University. The committee also advocated that the preparatory students were a part of the University and the students are entitled to instruction by University professors, alluding to the fact that professors were complaining about their teaching at the preparatory level.

Criticism

As the Latin School progressed and aged, criticism became an every day occurrence. Newspapers in Omaha caricatured the University as the "Lincoln High School", stated by Manley in his Centennial History. Besides outside criticism, within the University voices against the Latin School were heard loud and clear. Editorials in the The Hesperian Student were common. A complication of these editorials can be found on the Student Reactions page. The faculty of the University was also discontent with the Latin School.

Faculty Opinions

Although some of the faculty dreaded the preparatory department, they realized it was a necessity. To add to the longevity of the Latin School, professors sought to upgrade its course of study of the school in 1876 by adding Greek. It would now be studied for two years rather than one semester, with three years of Latin studied in two. The faculty gave recommendations of including higher English grammar, higher mental and written arithmetic, and local geography with map drawing in addition to what is already studied. The faculty proposals were adopted by the Board of Regents on June 21, 1876. However, later on the Board of Regents contracted their motion by rearranging the course of study. It was clear with this action that the Board was intent on maintaining lower levels of instruction in the Latin School. The Board of Regents still felt that secondary education in Nebraska was not sufficient enough to dissolve the Latin School or raise the academic level of instruction. Chancellor Fairfield also agreed with the position of the Board of Regents. He reminded the skeptics that many universities in the East had preparatory departments. Nebraska should not be ashamed to have a Latin School but rather, the University should concentrate on making the instruction reach its optimal level.

Growing Pains

With the high numbers of enrollment for the Latin School, there was a need for more instructional assistance in the preparatory department. The Hesperian Student offered to have more of the upperclassmen tutor classes, in the April 1876 edition. The paper's proposal was ignored. Nevertheless, the Board of Regents in March 1877 hired Miss Ellen Smith and Charles B. Palmer as full-time tutors of the Latin School. Another problem was the absence of leadership in the form of a Principal. Church was promoted to chair of Latin in the University in 1875 and from 1875 until 1877 there had been no one solely in charged.

Principal Palmer

During this position of full time tutor at the Latin School, C. B. Palmer founded and edited the , which happens to be Nebraska's first teachers' journal. spoke positively about Palmer in an editorial in their April 1877 issue.

On June 26, 1877, the Board of Regents appointed C. B. Palmer as the new Principal of the Latin School. In addition to this appointment, the Regents also outlined his responsibilities in his new position. His duties included the supervision of the entrance examinations and student discipline. This action by the Regents was significant because it is the first time since the establishment of the Latin School that the responsibilities and duties of the Principal were clearly stated.

Palmer Faces Problems

One of the problems that Palmer tried to address once installed in his position as Principal was that of the entrance examinations. He insisted that all applicants whether they were applying to the University proper or the preparatory department take the same exams. The faculty agreed with Palmer but, added that such exams should be administered to those who planned to pursue university work beyond the Latin School. Palmer managed to assert his ideas and because of the stringent regulation of the entrance examinations, enrollment into the Latin School dropped significantly. On the other hand, the scholastic standards of the preparatory department rose.

He also tackled the concern of the nature of the principal-ship position. The principal and faculty battled each other regarding the organizational and procedural jurisdiction. Does the Principal have total jurisdiction of the Latin School or should the faculty be able to lay claim to some jurisdiction? The faculty argued that Article 13 of the University charter which gave the faculty the prerogative to govern its own college and Section 12 which excluded tutors from membership in the faculty. It is clear that the faculty never really considered the higher tutors of the Latin School a part of the faculty. Without this respect, it is easy to see how the preparatory students would act towards the Principal. Palmer wanted to solidify his position's jurisdiction. This problem was never completely resolved.

Despite this set back, conditions improved temporarily. Student discipline and disciplinary action became more organized and defined. Students who missed class, or who were absent without permission reported to the Principal for disciplinary action, than to other faculty members. The function of the Principal as administrator, instructor, and counselor including a scholar was clearly defined and became a real position during Palmer's first year as Principal. During the reign of Palmer, the Latin School started to take on a strong identity as a preparatory school for the University. Regardless of the progress Palmer made for the Latin School, in June 1880, he was dismissed by the Board of Regents.

Transitions

With the departure of Palmer, Ellen Smith remained a full-time tutor. There was a breakdown in the discipline of the students and there were suggestions of reorganizations. Chancellor Fairfield headed the Latin School to try and abide the rising problems. Soon the Board of Regents came to his aid.

Ma Smith

Miss Ellen Smith became principal of the Latin School in 1882. She was made adjunct professor of Latin in 1883. She was not only the first female faculty member of the University, but she also was the first woman with a right to vote in faculty meetings. She had a passion for her work and connected well with the students. The collegians called her "Ma Smith" because she was such a motherly and influential figure for them. After her position as principal, she became the Registrar of the University and held that position until her death in 1903.

As the only woman principal of the Latin School, Smith confronted numerous problems and tried to correct them. She brought the discipline the Latin School lacked in the time after Palmer's dismissal. She requested more assistance in instructing the students. The Board responded by electing Miss Madge Hitchcok to be a full-time tutor in the Latin School. Smith also tackled the issue of entrance examinations and wanted every student wishing to enter to be well-prepared in all the studies required. The exams now became stricter.

A milestone in her Principal-ship was Smith's campaign to have the right to vote during faculty meetings. As mentioned above, she was granted that wish. David Henry Bergquist, in his thesis affirmed that Smith's "careful attention to duty, her strong defense of her administration against criticism, her concern for quality student work, and her penchant for quality instruction, moreover, helped to sustain and strengthen the Latin School through a difficult period in University history- a period in which the University was without a chancellor" (79).

Desire to Eliminate

From the very beginning of the Latin School, there has been opposition against its existence. The faculty was very vocal in their opinion against the Latin School. The quality of secondary education was rising in Nebraska so the faculty committee conducted a survey to make the secondary schools the replacements for the Latin School. This led to rumors that the preparatory department was going to be abolished. The Hesperian Student reacted to the surfacing rumors that plagued the campus. It was in favor for the demise of the department; however, the Chancellor abated all the rumors. The Board of Regents confirmed that the Latin School was not going anywhere and supported the existence of the school.

Although the Regents supported the Latin School, the new Chancellor Manatt was in favor of the abolishment of the department. He stated that by law the Latin School was not a part of the University and that it would be discontinued as soon as possible. He felt that the preparatory department was not fulfilling its desired purposed when it was established. Although the Chancellor was against the Latin School, under the principal-ship of Charles Bennett, the preparatory department still flourished. Manatt increased the level of scholarly learning at the University to compensate it for being around. Bennett helped the Latin School develop further.

Dr. James T. Lees

James Lees was the last great principal of the Latin School before its demise. He succeeded Bennett in 1889. He continued the work of Manatt and Bennett. He did face problems when the public schools were doing the same work as preparatory department. Lees managed to conduct the influx of preparatory students by maintaining the integrity of the school. It was inevitable that the Latin School was soon to fall. Lees was appointed chair of the Classics department and continued his career at the University in this position. He has published numerous works and is one of the accomplished principals. His memorial is on campus by Architecture Hall.

| Picture of the memorial stone of Dr. James Lees |

The Demise of the Latin School

The public schools within the state of Nebraska were starting to prove that they were capable of taking over the preparation into the University. Chancellor Canfield also realized this notion. The public schools were doing the same work as the lowest level of the preparatory department. Due to this discovery, the first year of the Latin School was abolished. The Board of Regents also noticed the rise of public schools. The established idea of abolishing the Latin School was made in 1895 when the Nebraska Legislature made public high schools free admittance. The decision of the Board to abolish the Latin School in general came in 1898 with the last graduating class of the preparatory school. It is clear that the preparatory school was no longer needed. For the years the Latin School was in existence, it educated many notable alumni and made a lasting impression on the University of Nebraska. It helped the young University come into adulthood.

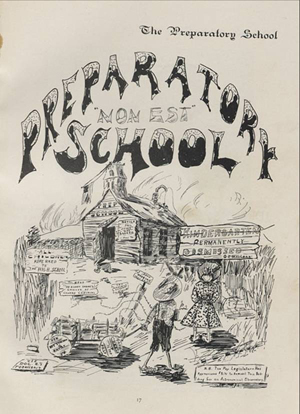

| Preparatory "Non Est" School |

|