Projects

History of the UNL Science DepartmentsProject Editor: Susannah Hall, UCARE, 2008 Table of Contents

The Botanical Seminar

|

The Botanical Seminar

The University of Nebraska saw several significant scientific communities develop at the end of the Nineteenth Century, when the University was just beginning to come into its own as a serious collegiate institution. Communities like the Botanical Seminar and scientific club (discussed elsewhere in this project) pushed the science departments, both faculty and students, away from rote memorization and towards groundbreaking research. They encouraged members of the community to learn and contribute, and developed a scholarly camaraderie which eventually circled the globe. These scientific communities influenced the rate and direction of the university's growth and helped to define the departments' aspirations and purpose.

Scientific coursework, for more than a decade at the beginning of the University's existence, entailed memorization of two or three main textbooks. Students could choose between a few courses of study for their four years at the school: the Classical Course or the Scientific Course, or later on an Arts Course. The "Science Course" had different requirements over the first few decades, but these usually included four languages, more than twenty classes in history, literature, philosophy, and rhetoric; and only 16 or so math and science classes. During the 1880s, after the construction of Chemistry Hall, some laboratory coursework was added, but classes were few and ill-equipped. The minimal requirements resulted in students who could recite pages of textbooks, but not necessarily analyze any scientific problem they had not been taught. The agricultural campus, affectionately dubbed "The Farm", changed this slightly, but the University was struggling to gain prominence and accreditation from peer institutions and the state. The building of scientific communities helped the school to attain these goals.

One of the science clubs at the University of Nebraska, undeniably influential in the rise of scholarly research and scientific rigor at the university, was the Botanical Seminar. The Sem Bot (as it was affectionately called) came into existence October 11, 1886. Although it is often stated that seven students founded the organization, the first year's roll includes only five students-J.G. Smith, H.J. Webber, J.R. Schofield, J.A. Williams, and Roscoe Pound-who decided to test each other above and beyond the regular rigors of scientific study. The next year's roll includes A.F. Woods, J.H. Marsland, and L.H. Stoughton.

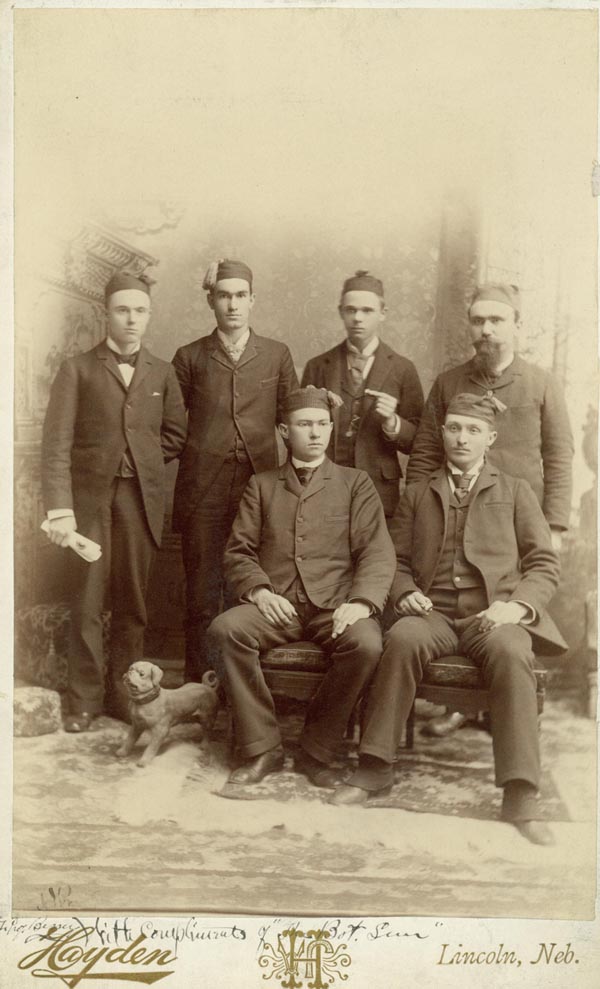

Woods Marsland Pound Schofield

Smith Wilhauer

The Sem Bot - 1890

|

Once a week, they held convocation, where one or two students would read original papers, and the other students would then critique and question the writers. Since the topics of the papers were announced six weeks in advance, the students were thoroughly prepared to rip the presenter's position to shreds. This, of course, prepared the students for stringent scholarship and promoted well-studied, well-researched papers, not to mention any later publications. In a hopeful manner, the Secretary added a section headed "Publications" to each year's "Chronicle". It was empty for the first six years, but the aspirations were there.

However, the rigors of convocations were slightly misleading: the Sem Bots were anything but dry and reclusive. The men enjoyed "tossing lits" in tussles with students from the literary societies, composed songs on botanical subjects, and ate "Canis Pie", traditionally filled with mincemeat, presumably never actually made with dog. Under Professor C.E. Bessey, these students, not all of whom originally focused on or continued in Botany, established a long-standing, somewhat irreverent society.

According to the official records of the Sem Bot, the year 1888 "was the most prospered year of the Sem Bot. The greatest enthusiasm was manifested by all, both in Botany, and in the persecution of lits. Regularly after each convocation one or more lits were tossed, and the tossing of lits and consumption of CANIS PIE became so common at the Lab. as to cease to attract attention. In the Scientific Club, too, the Sems were completely dominant, filling the programs and electing officers as and whom they pleased."

After proceeding for several years in this manner, the Sem Bot began to feel their work could simultaneously educate other members of the university and state. In 1889, the Sem Bot undertook to develop the Botanical Survey of Nebraska. Initially they planned a severe rewriting of Samuel Aughey's Flora of Nebraska, commonly viewed by faculty and students as an ill-researched, error-ridden shame to have as the university's first publication in botany. Determined not to be accused of the same lackadaisical approach to scholarship, the members went out into the state, collecting specimens for verification, and paving the way for even more work on the subject in subsequent years. They were so thorough and dedicated that R. Pound earned his MA for organizing and directing it, and some of those early specimens remain in the Nebraska State Museum collection still (a tribute to their preservation).

The Sem Bot also encouraged professors to expand their repertoire. In 1886, F.S. Billings taught the first course on animal disease. In 1888, the Sem Bot asked Professor Lawrence Bruner to outline a course in insect fauna. He taught the university's first entomology course in 1890, and by 1895 established the Department of Entomology & Ornithology. Bruner also established a standard for international cooperation in ecology by journeying to Argentina at the request of that country's government, in 1897, to fight grasshoppers. In 1893, Henry Ward taught the first laboratory class in parasitology in the Western hemisphere. Also in 1893, the Graduate College officially came into existence. In 1896 Instructor Herbert Waite organized the Department of Bacteriology.

Later, the expanded colloquia functioned as a continuing education program for faculty, and supplementary lectures for pupils. The Sem Bot lectures encouraged students and professors to learn outside their primary areas of focus. The constant pressure on readers to take a new position or find new insight inspired research projects in the department and fostered a higher level of scholarship by undergraduate and graduate students. The graduate program itself developed into maturity during the first decade after the Sem Bot's foundation: the first A.M. was awarded in 1886, and the first PhD in 1897.

Convocations & Banquets

As more students joined, and members graduated, the society expanded to include graduate students in 1888, and faculty members beginning around 1890, mostly to accommodate members who attained these positions. The meetings came to entail certain traditions, especially during the first open convocation of the year, where a banquet was often held. The dishes on the menus were written in their two-part Latin botanical or zoological names, according to the Linnaean system. The toasts for the banquets were equally entertaining: on 21 November 1891, a banquet was described thus in the Records of the Sem. Bot.:

| | "The Chancellor" | Roscoe Pound, Toastmaster | | Response by the Chancellor | | "The Sem Bot & the Department of Botany" | Dr. Bessey | | "The World We Live In" | J.G. Smith | | "The Perfessor" | J.H. Marslaud | | "Boys" | Prof. Bruner | | "CANIS PIE!!!" | The L.W. (A.F. Woods) |

After the toasts, "A feeble attack by some lits was ignominiously put to flight, the lits losing their hats, and at the close of the banquet a magnificent UNDULATOR was sent forth upon the midnight air."

The Undulator & Canis Pie

The Undulator and its meaning were described in by Edith S. Clements "Our Botany Trip" in 1909:

When the long wailing notes of the Sem. Bot. undulation rose on the June air, heads were thrust from windows of the oncoming train in startled surprise, and even the townsfolk stopped to listen. Etiquette demanded a like response, and after scrambling aboard with much laughter and some curses at encumbering luggage, we rushed to the rear platform and sent wavering back towards the disappearing lights of the city those same mournful notes so intimately associated in our minds with aspirations towards scientific attainment, and huge sectors of mince pie:

Peye-eye! Ca-nis! Peye-eye!

Whoop-ee!

Show! Me! A! Lit!

Non-cum-dipteris-

dor-sal-i-bus-

afflicti--s-u--m-u-s!

|

"I like that song,' said Babe as we sought our Pullman seats and sat down to recoer from the hurry and excitement. 'It makes little prickles run up and down my spine. But what does it mean anyhow?'

"That, my dear child,' answered Dad [R.J. Pool], who hopes some day to be a professor in the University, 'represents the learned way in which the learned members of the most exalted Botanical Seminar of the University of Nebraska express their articles of faith. 'Pie-well, er-that's merely pie-not 'pie-eye' you understand; it's necessary in order to chant in the approved Gregorian manner, though it's quite unlikely the monks of that day were acquainted with pie...'

"Poor things, murmured Nell. "No wonder they retired to monasteries and invented such doleful wailings."

"Canis," continued the lecturer, ignoring the interruption. "Who remembers enough Latin to tell what that means?"

"I know. I know, teacher," cried Nell, waving her hand in the air. "Can-is, can-e, can-em, dog. But where does the dog come in?"

"In the pie, of course, though it tastes better under the name of 'mince-meat,' which is the regulation filling for the pie consumed at our high and mighty feeds. 'Show me a Lit.,'" continued Dad, "means that if a scientific student means a member of a literary society on a dark night, the latter should jolly well look out. But the gist of the whole matter, Little One, lies in the final statement which, though here appearing in purest Latin, means in vulgar parlance that 'there are no flies on us,' the truth of which assertion we are one and all pledged to maintain to the bitter end."...

Membership

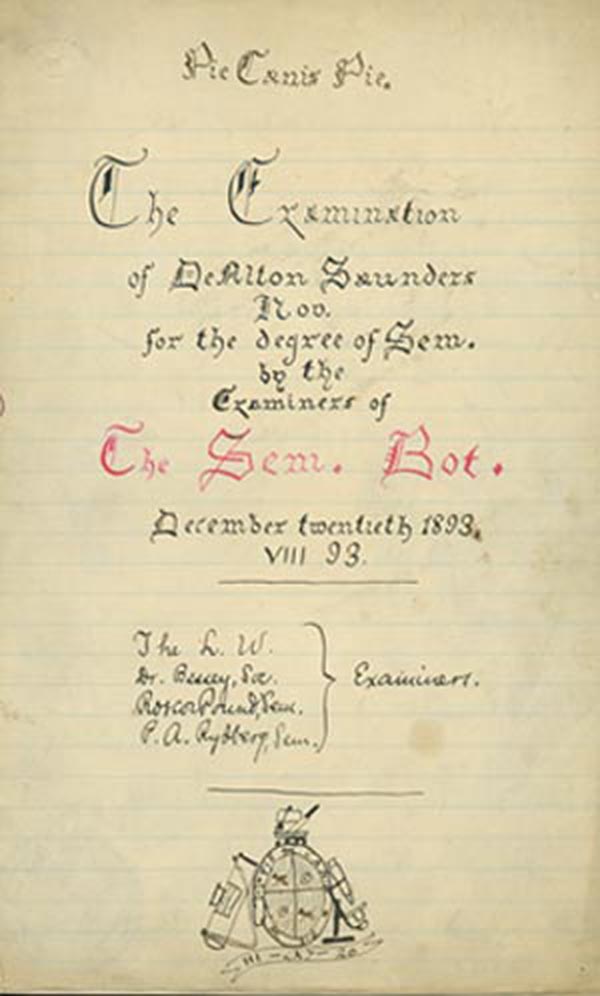

The structure of the Botanical Seminar was designed with a Lord Warden (LW) over the Honorarii, Ordinarii or Seminarii, Novitii, and Candidati. In order to officially become a member of the Sem. Bot., or to attain a higher level of membership, the candidate was required to pass a written examination and an oral defense in front of a committee of examiners. A great deal of effort went into each examination, both by the examinee, and the examiners, who constructed the packets by hand for the first ten years of the Seminar's existence. Below is the examination packet cover for D.A. Saunders to become a Sem. in 1893.

| Examination Packet for D.A. Saunders - 1893 |

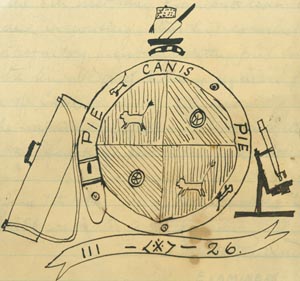

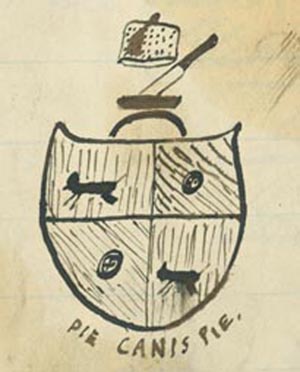

The seal of the Sem. Bot., shown at the bottom of the above cover, changed often. Other forms seen throughout the years included:

| Seal - C.A. Turrell Candidatus 1894 |

and

| Seal - D.A. Saunders Candidatus 1893 |

The simpler figure was adopted for general use as drawing individual seals in meticulous detail for every examination and piece of correspondence became impossible.

| Seal - Sem. Bot. Letterhead |

The 10th Anniversary

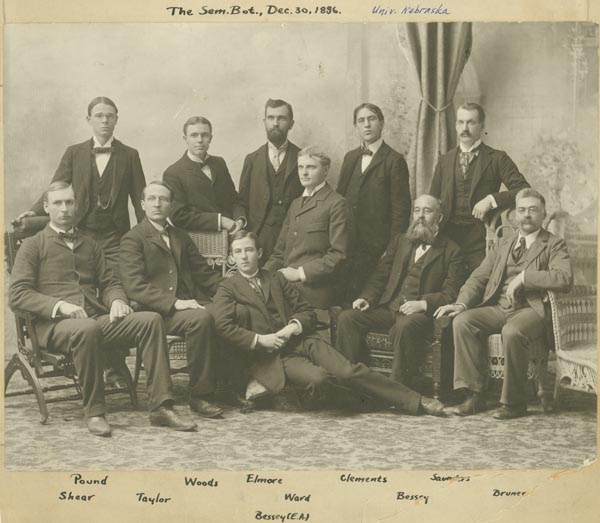

By the tenth anniversary, the Sem. Bot. had developed from a student-centered group to include a significant number of faculty. The following photo was taken December 30, 1896.

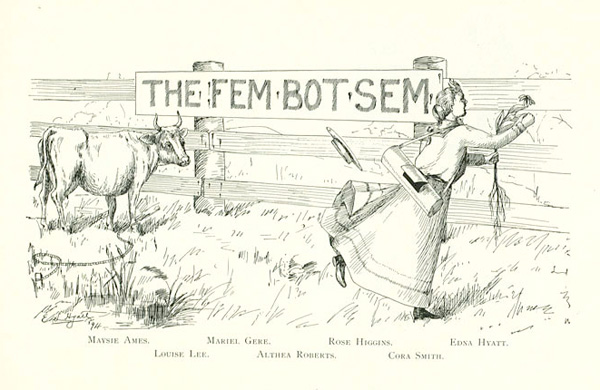

In June 1898, the Sem Bot directed "patents of precedence" to eight women, the first women mentioned (except when describing the quality and origin of pie) in the record of the Sem Bot. Women had initially been excluded from the club along with graduates and faculty; they formed the "Fem Bot Sem" during the mid 1890s. It functioned as a coed "rebel coalition" until the women were allowed membership in the second half of the 1890s. One of the only records of this society's short existence is in the 1895 Sombrero, where this picture appeared near the official Sem Bot entry. Later on, women came to play a dominant role in the society, holding leadership positions.

Of course, by the late 1890s the original members had begun to go their separate ways. Most earned graduate degrees, and collectively their scholarly travels spanned the globe. The club expanded from its original selective group of undergraduates. Visits to Lincoln by old members were celebrated usually by a meeting at the train station, a small banquet and colloquium in their honor, and a thoroughly practiced ritual of Canis Pie and the Undulator. Since many of the students went on to become faculty elsewhere, they were able to carry these traditions to new destinations and often founded similar clubs at other universities.

Many of the students had taken on teaching positions at the University of Nebraska itself during the 1890s, and so the club had expanded to include many faculty members. Almost, if not all of the Botany department faculty members were in the Sem Bot during parts of the first twenty years of the new century. The new faculty were rarely put through the thorough examination procedure endured by earlier members, but the amity established by the club strengthened both the department and the scientific community as a whole. For the most part, the Botany department had lower faculty turnover during than the other science departments of the period. It is interesting to note how long many of the professors who joined the department in the early twentieth century stayed at the University: Dr. Pool was associated with the department until 1956; Emma Andersen taught at the university until the 1960s; the Walker sisters, Elda and Leva, taught for over half a century each. Also, the developments in the Botany department promoted a healthy sense of competition within and without the department. Other sciences expanded their efforts and programs in order to achieve funding and results comparable to the Botany departments. This was somewhat difficult when the Botany department had worked so hard to assemble strong relationships with the administration of the University. The presence of the Chancellor and other high-ranking officers of the system at banquets indicates the University's involvement in the department and the Sem Bot. As is often the case, involvement implies investment, and the strength of the program by the time of the twentieth anniversary was impressive.

The 20th Anniversary

On October 11, 1906, the Sem Bot celebrated its twentieth anniversary. An article appeared in Science in December (Volume 4, Issue 101, pp. 822-825) describing the successful organization and its history. At the celebration, C.E. Bessey gave a speech, wherein he addressed the purposes behind the Sem Bot. Although the full text of the speech was not transcribed, his notes remain:

"Canis Pie & Meristem: 2 very important things--"

1. Canis Pie- Contributes to bodily support, giving strength, tone, vigor.

- Made of vegetable & animal, i.e. Biological

- Always a:

- --mixture

- --mystery

- The Eater is an investigator.

2. Meristem- --is growing

- --may develop

- --may change

- --may take new ideas

- --is not fixed

- --Meristem is youth

- --Permanent tissue is Old Age

- --Be Ever Young

- --Don't grow old

- To sum up: "Keep yourselves so that you may grow, and not become fixed. Keep an abundance of mental meristem, and avoid acquiring too much permanent tissue. Have a bias for the new and untried."

Dr. Clements also gave a speech, warning botanists that as the field expanded and developed, the method of research would shift. He noted that laboratory work would soon become secondary to field work, and the shift of emphasis would require changes in teaching style, instruments, base stations, and the construction of greenhouses rather than laboratories. Clements' foreshadowing of the future of botany also applied to the future of the Sem Bot.

Sem. Bot. Songs & Poems

As previously mentioned, the Sem. Bot. members composed many songs on botanical subjects. Following are several songs in honor of Canis Pie, and a poem on "The Bacteriological Ball".

PRUNUS PIE SONGS

On Nebraska's prairies rolling

Prunus besseyi hides its leaves

Flowers in sessile umbels spreading

On the sand a picture weaves

Prunus besseyi we invite you

With they fruit so round and black

Sem Bot pie feed our just due

Fill each mouth without a lack

|

Gilmore found it rich and shining

Filled a sack and brought it back

Walker made a pie crust melting

In our mouths when pushed within

Sweet and juicy Canis Pie

Full of hard things too we find

But for all we will not die

More and more of every kind

|

------------------------------V.W. Pool, tune Love Divine, etc.

Plebean cares they all are dead

We ne'er shall seek them more

They fled when first we ate the pie

From Prunus besseyi

|

Oh Canis Canis Canis Pie

We all shall eat it more

We'll eat the Canis vera pie

And pseudo-canis too

|

Oh Prunus besseyi we'll eat

And hope by it to grow

In botany as great to be

As Bessey and some more

|

So pseudo-canis besseyi

And Malus we'll eat too

Cucurbita completes the list

Of pseudo-canis pie

|

For canis pie we meet tonight

And pseudo-canis pie

We'll take a slice of Prunus pie

Of Prunus besseyi

|

------------------------------E.R. Walker, tune Auld Lang Syne

|

"The Bacteriological Ball"

A gay bacillus to gain her glory,

Once gave a ball in a laboratory.

The fete took place on a coverglass,

Where vulgar germs could not harass.

None but the cultured were invited,

For Microbe Chicks are well united.

They closely shut the ballroom doors,

To all the germs containing spores.

The staphylococci first arrived,

To stand in groups they all contrived.

The Diplococci came in view,

A trifle late and two by two.

The Streptococci took great pains,

To seat themselves in graceful chains,

The Pneumococci stern and haughty,

Declared the Gonococci naughty,

And said they would not come at all,

If the Gonos were present at the ball.

The fete began, the mirth ran high,

With not a fear of danger nigh.

Each germ enjoyed himself that nite,

Without a fear of a phagocyte.

'Twas getting late and some were loaded,

When bang! the formaldehyde exploded;

And drenched that happy dancing mass,

That swarmed the fated coverglass.

No one survived but perished all,

At that bacteriological ball.

---------------------------------------Mailed in by Ruth Weinard

|

The Decline of the Sem Bot

After Bessey's death in 1915, the leadership of the society passed to R.J. Pool, who had indeed become a Professor at the University. As the size of the club grew, however, its rigorous demands decreased, and the club became less inclined to toss lits and employ the Socratic Method. The tradition of pie remained, but the important aspects of its consumption and symbolism were all but forgotten. By the late 1920s, the club had degenerated into more of a social scientific club, with its student leader Julia Joyce Harper even petitioning to surviving original members to change the society's name to "Sigma Beta" according to the Greek-ification trend of the period. Roscoe Pound responded to Ms. Harper in May, 1924: "For my part, I should say go on with the Botanical Survey; go on with the Flora of Nebraska; do some big things for botany and let the wearing of pins and sporting of Greek letters be done in connection with some other organization." The society dwindled, however, as the expansion of summer programs to Cedar Rapids and the Black Hills rendered many of the convocations and colloquia superfluous. Students and faculty could travel and learn beyond the campus much more easily, and the smaller groups created within these programs were easier to develop than the expansive ranks the Sem Bot included at its peak, around 1920.

However, the catalyst had served its purpose: it inspired a research-based botany, and later on, biological sciences department. It would be betraying the scientific term catalyst if one did not acknowledge that it was necessary to accelerate this reaction, but was not part of the end product. The Sem Bot, like many other professional societies, faded into oblivion during the 1930s, when scholarships and salaries dwindled significantly. It no longer appeared in the Cornhusker annual after 1931, and the records discontinued after 1936.

The Sem Bot Creed

"I believe in a vegetable kingdom of which the Myxomycetes are not a part. I believe in the Bessyan system of classification. I believe in the nutritive qualities of Canis Pie. I believe in the Schivendenerian algo-lichen hypothesis, in the heteroecism of rusts, in the law of priority, in the use of parentheses in nomenclature and in the decapitalization of specific names. Frigida dies est cum relinquemur! or "Feeble is the day when we are left behind!"

|