Projects

Project Editor: Amber Harris Leichner, English 418/818, Fall 2005

Aaron Douglas at the University of Nebraska

In the spring of 1922, Aaron Douglas became the first African American to graduate from the University of Nebraska with a bachelor of fine arts degree. During his time at the University, Douglas won the respect of his instructors and peers as well as a first place prize for drawing from the Fine Arts Department. His success at Nebraska became the foundation for a career as one of America's foremost 20th-century visual artists, and his name is forever linked with the the Harlem Renaissance—the period of vibrant African American cultural, artistic, and political activity that roughly spanned the years from the armistice of WWI until the Great Depression.

Aaron Douglas was born on May 26, 1899 in Topeka, Kansas to Aaron senior, a baker, and Elizabeth, a homemaker. As members of a small but active black community in Topeka, the Douglases shared the values of racial uplift and social progressivism with their neighbors (Kirschke 3). As young boy, Douglas was impressed by his mother's talent for drawing. His own skill as an artist was exhibited in his early interest in color and shade, and his enthusiasm for art was not discouaged by the fact that a career in art was not a stable or accepted profession for African Americans during the early decades of the 20th-century (Kirschke 1). Douglas attended segrated elementary schools as well as an integrated high school. But he also supplimented what was missing in his education by reading what he felt where essential literary texts, including those of Emerson, Bacon, Montaigne, Hugo, Dumas, Shakespeare, and Dante (Kirschke 3). This motivation for self-betterment despite the climate of racial tension in the northern cities, increased lynchings and Ku Klux Klan activity in the South, and widespread segregation across the United States, would characterize Douglas's intellectual and artistic success throughout his life as he pursued his career as an artist and teacher.

Knowing college would be necessary for his achievement but that his family could not afford to pay for his tuition, Douglas set out for Detroit after graduating from high school, where he worked in the auto factories for a period of two months. While there, he took advantage of the free art classes offered in the evenings at the Detroit Museum of Art. When he returned to Topeka in 1917, Douglas had "$300 saved and new clothes suitable for wearing to college" (Kirschke 6). Though he briefly considered the law as his profession (Kirschke 3), Douglas eventually enrolled in the Univerity of Nebraska's fine arts program in 1918.

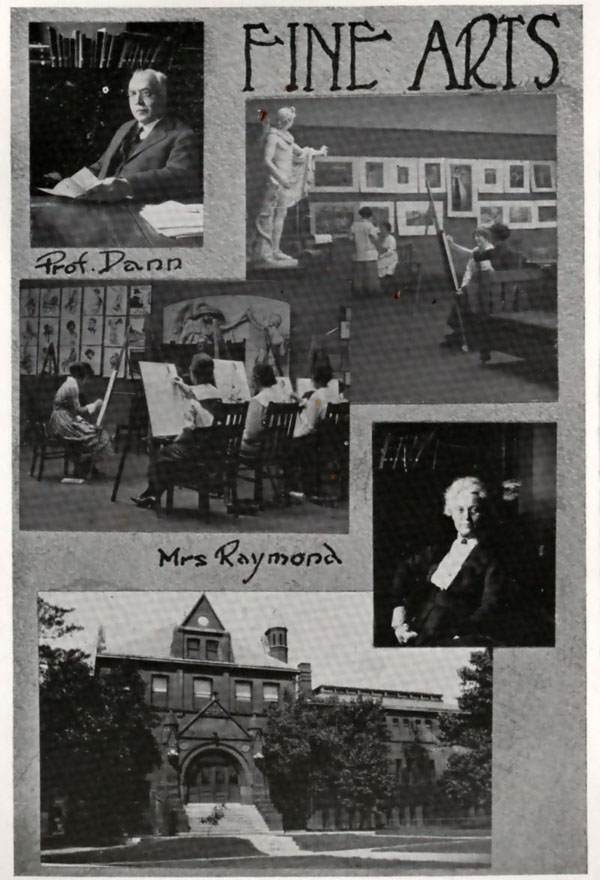

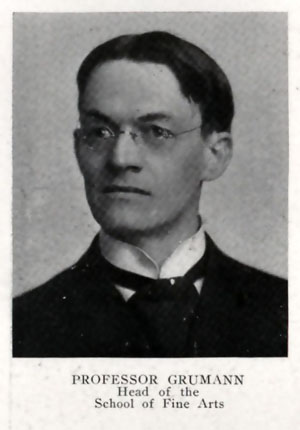

As self-determined and ethusiastic as he was, "Douglas had little understanding of the rules or format of a university eduatcion. He arrived ten days into the term, unaware what day classes began" (Kirschke 6). But despite his rough start at Nebraska, Douglas was supported by the director of the Fine Arts Department, Paul H. Grumman,

who accepted the inexperienced student conditionally until his records arrived from Kansas. Later Grumman would recommend courtesies be bestowed upon Douglas in , evidence of Grumman's sustained as an artist and his wish for Douglas's continued professional success.

PROFESSOR GRUMMAN

Head of the

School of Fine Arts

|

Douglas supported his education at Nebraska by working as a busboy during the school year as well as a laborer during the summer breaks between terms. But WWI interupted Douglas's college studies, the young student felt compelled to volunteer for service in anticipation of the draft. His was a member of a Nebraska unit called the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), and he was active in it for several weeks until he was informed by his regiment commander that his service would no longer be necessary. Douglas suspected that his dismissal was racially motivated, and the experience was a humilating one. He would find a more accepting environment in the SATC at the University of Minnesota, where he stayed until the conclusion of the war(Kirschke 7).

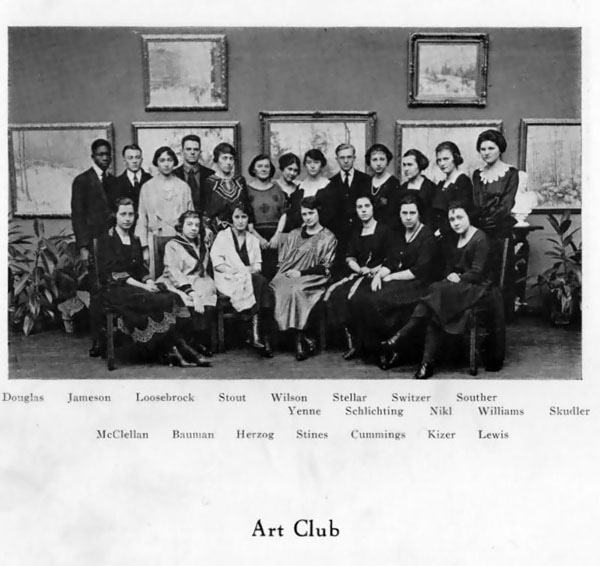

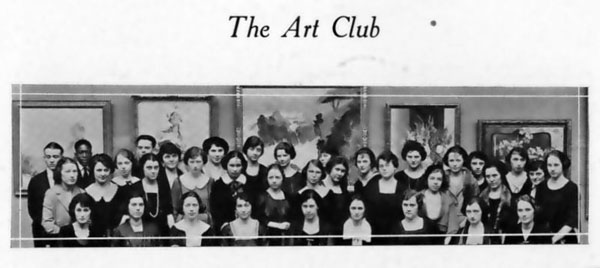

Upon his return to Nebraska, Douglas participated in the

as well as a professional African American business fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi. During this period he was also actively interested in the dialogues taking place in the pages of the dominant black periodicals of the period, The Crisis, published by the NAACP and Opportunity, published by the Urban League (Kirschke 8). In the pages of these magazines he learned about Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA); the philosophies of the leading African American intellectuals, such as the editor of The Crisis, W.E.B. DuBois, and Howard University Professor and the first black Rhodes Scholar, Alain Locke; and, perhaps most important, pages filled with essays, fiction, poetry, and art produced by African Americans for an African American audience. By the time of his graduation, Douglas had earned his bachelor of fine arts degree and met with success in his courses; he also deepened his sense of pride in his racial heritage and honed his political consciousness.

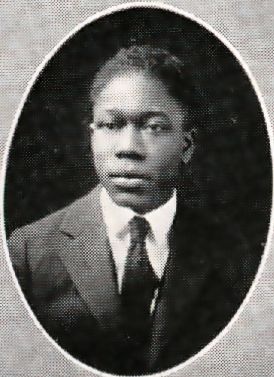

Aaron Douglas

1922 Senior Yearbook Photo

|

With his degree in hand, Douglas found a position teaching art at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri where he also enrolled in a correspondence course in commercial art (Kirschke 9). But shortly after the close of his first year of teaching, Douglas moved to New York City, where he hoped to stay only long enough to then set out for Paris, the city he saw as essential for any student of art. Douglas became one of the hundreds of thousands of blacks across the country, and especially the Southern states, drawn to the Northern cities and the heart of the intellectual and cultural movement of Black America: Harlem.

Upon his arrival in New York City in 1925, Douglas's friends and acquaintences urged him to stay in Harlem and dedicate himself to his art in the teeming city where the era of the New Negro was dawning. Before long Douglas was illustrating issues of The Crisis and Opportunity, and was recruited to create woodcuts for the seminal publication of the Harlem Renaissance, The New Negro, edited by Alain Locke. This collection of essays, poetry, and fiction helped to define the aims of black artistic productions, foremost of which was self representation. Douglas, like Locke, subscribed to a new artistic philosophy that sought to represent and define black culture in the U.S. while also asserting that "the New Negro not only had soemthing positve to contribute to American life but had, indeed, ascended to new cultural heights" (Campbell 16). In his work, Douglas cultivated themes that were relevant to blacks in America and often incorporated African imagery into his drawings, paintings, and woodcuts. The "primative" style Douglas utilized during the Harlem Renaissance period came to embody the era itself.

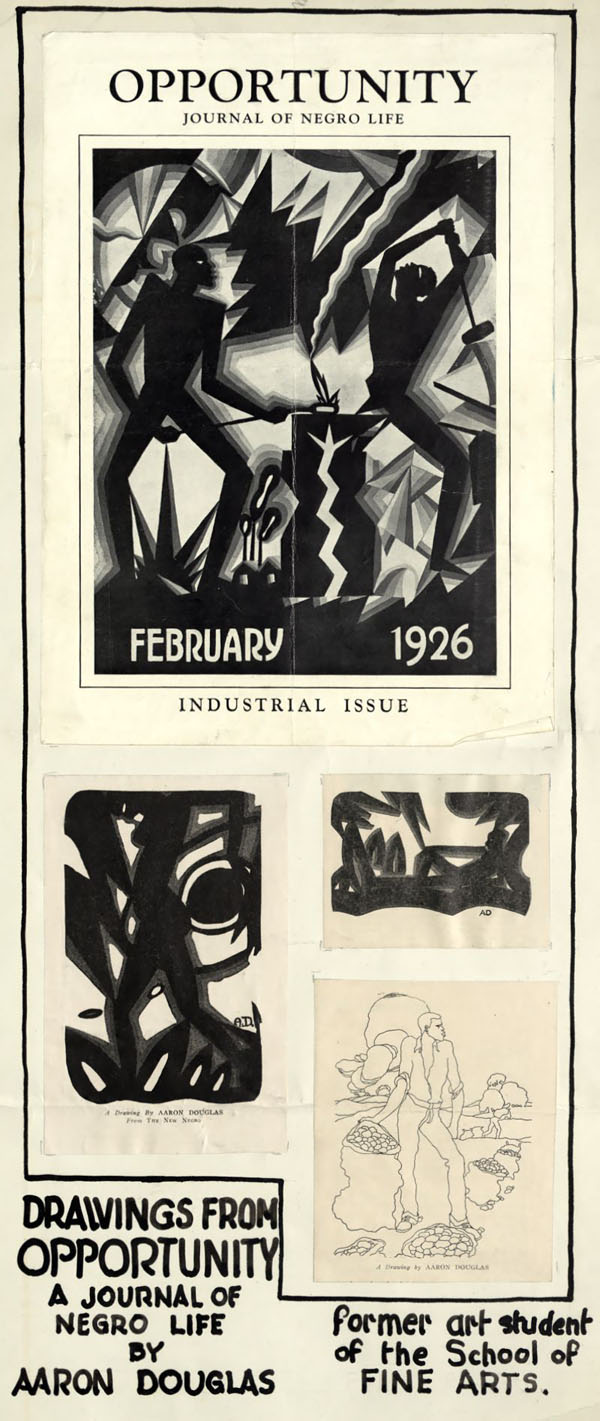

While Douglas's works began to reach a wide audience, people in Lincoln took notice, as evidenced by this poster made by the Fine Arts Department:

OPPORTUNITY

Journal of Negro Life

FEBRUARY 1926

INDUSTRIAL ISSUE |

In October of 1927, two brief articles appeared in the University's student newspaper, The Daily Nebraskan, announcing the fact that Douglas had illustrated James Weldon Johnson's highly acclaimed book of poetry, God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. The appeared on October second. The followed a few days later, on the seventh, and quotes the favorable review of Johnson's book by Survey Graphic. Contributing the illustrations for God's Trombones was an accomplishment that would remain one of the highlights of Douglas's artistic career.

By 1936, Douglas had become a leading figure in the African American art community, and the Nebraska Art Association was proudly displaying his paintings, the oil "Window Cleanings" and the water color "Eigth Ave. Market" in its March 1936 art exhibition at Morrill Hall on the University of Nebraska campus. He is briefly described, along with the exhibition itself, in "Window Cleaning" must have made a positive impression on members of the Nebraska Art Assoiciation, which included faculty of the University's Fine Arts Department, because the . The purchase of Douglas's work was announced in the .

Douglas finally left Harlem in 1937 to found the art deparment at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he taught until his retirement in 1966. As a professor he had much influence over generations of students. One such student, Gregory Ridley, recalled in 1988 that "through Douglas's teaching approaches, he domonstrated that artistic expressions did not spring full-blown from either the head or the heart but evolved from artists' conceptions of their roots (Ridley 42). Ridley's statement seems to present Aaron Douglas as an artist and teacher who never forgot where he had come from and what heritage he proudly claimed as an artist and a man. Today the University of Nebraska claims Douglas as an alumus of great disctintion, who was a pioneer on a Midwestern campus that thought of him as a "colored man of unusual qualities," as Paul H. Grumman put it in his letter to Professor Kurtzworth. In January 1942, Douglas's continued success as a "famous Negro art graduate" twenty years after receiving his degree was noted in .

Works Cited"Aaron Douglas, Famous Negro Art Graduate." Nebraska Alumnus. Jan. 1942: 8. Anderson, Emma and D. Gross. "Critics Praise Work of Negro Artist and Poet." The DailyNebraskan. 7 Oct. 1927: 1. "Douglas, Graduate of School of Fine Arts, Lauded for Drawings." The Daily Nebraskan.

2 Oct. 1927: 3. Campbell, Mary Schmidt. "Introduction." Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America.

Ed. Mary Schmidt Campbell, David Driskell, David Levering Lewis, and

Deborah Willis Ryan. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987. 1-55. Gerhart, H. L. Cornhusker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1920. Kirschke, Amy Helene. Aaron Douglas: Art, Race, and the Harlem Renaissance.

Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995. Landale, J.A. Cornhusker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1921. "Painting." Nebraska Alumnus. May 1936: 16. Ridley, Gregory. "Aaron Douglas: A Student Remembers." The Langston Hughes

Review. 7:2 (1988): 42. Randol, Ward M. Cornhusker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1922. Townsend, Wayne L. Cornhusker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1918. Wenger, Robert S. Cornhusker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1919.

|