Texts

Project

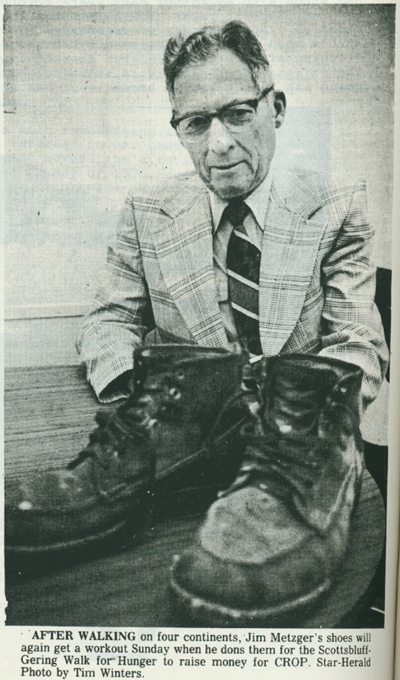

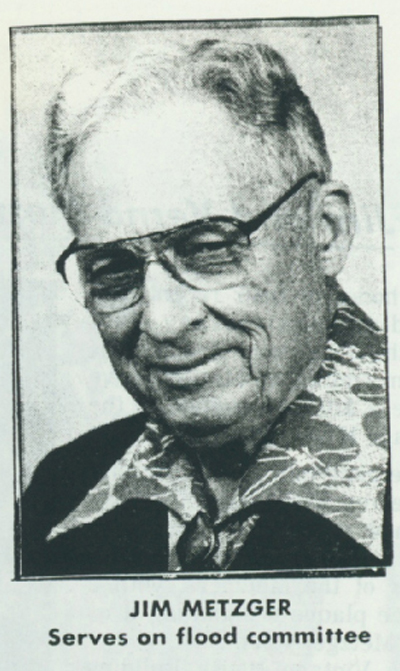

Editor: Jim Metzger

|  | | | Page Image | |

Metzger Memories

|  | | | Page Image | |

Metzger Memories

|

This story is dedicated to the Lady that has

influenced my life since I first met her in 1925.

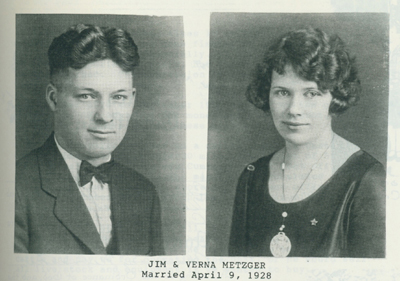

VERNA PIELSTICK METZGER

She has traveled the route with me, thru the difficult

years of depression and to many lands. She gave up a

profession of her own, to raise a family of four. She has

kept diaries and other records that have made this story

possible. She has always said, "You can do it."

|

JIM METZGERSeptember 1, 1994

Sonoma, California.

|  | | | Page Image | |

FOREWORD

This is a record of events in my life, that were

written over a period of 6 years, 1988 to 1994. It began

with a writing class sponsored by the Santa Rosa Junior

College. When the college dropped the course, the class

persuaded Rebacca Latimer, a published author, to be our

instructor. Her suggestions, and interest in Turkey have

been major contributions to this story.

An attempt has been made to keep events in sequence,

but some events and places that were part of my early life,

have also been apart of later years. The early dates have

been taken from school records from 1914 to 1924.

Records that Verna kept, and those from the period

while on the ranch, covers 1928 thru 1932. Project reports

and travel orders while with the CCC camp and Soil Conservation

Service are for the period from 1934 to 1944.

Farm Management and Insurance records, while living in

Gering Nebraska and Longmont Colorado, are from 1945 to 1955.

Our assignment overseas from 1955 to 1967 was with the

Agency For International Development, (USAID). Verna's

letters to the family, the scrap books she kept and our

passports, supply the dates for this period.

The years from 1967 to 1976, spent at Scottsbluff,

Nebraska, were semi-retirement. I renewed my Insurance and

real estate licenses and worked part time.

In 1976 we moved to Sonoma, California. I passed

California examinations for licenses I had in Nebraska

and Colorado, but spent most of my time as a volunteer

with the Chamber of Commerce and community projects.

An assignment in Cali, Colombia, with the International

Executive Service Corp. (I E S C) was among the volunteer

activities.

Our return trip to Turkey in 1982, gave us an opportunity

to renew friendships with my two "Counterparts", Naki Uner and

Atif Atilla, and Verna met two of her former students, who were

teaching at the school where she taught.

Included also, among the writings, are glimpses of my

thoughts on life in general, and the philosophy by which I

have lived.

|  | | | Page Image | |

| CONTENTS | | My Parents | 1 | Government To Private | 48 | | My Brothers | 3 | Safflower | 49 | | Country School | 4 | Howard Finch | 50 | | One Room School | 6 | Turkey 1955 | 51 | | Prairie Fire | 7 | Orientation | 52 | | Odessa | 9 | First Day In Izmir | 53 | | Food | 10 | Ishan Candas | 54 | | Eggs | 11 | What Is An Advisor | 55 | | Red Shirt | 12 | Small Equipment | 56 | | No Cash | 12 | English To Turkish | 59 | | Trans. To School | 13 | Hotels in Turkey | 60 | | Pest Control | 14 | Elmali | 61 | | High School | 15 | Izmir Hotel | 62 | | Deep Snow | 16 | Turkey To Jordan | 63 | | Pumps & Windmills | 17 | Amerikan Kiz Koleji | 63 | | Early Winter | 18 | East Ghor Canal | 64 | | Filling Ice House | 19 | The Volkswagon Bug | 65 | | Drinking Water | 20 | Tadmore | 66 | | Rattlesnakes | 21 | Nepal | 68 | | Harvest time | 22 | Jordan To Nebraska | 69 | | Husking Corn | 24 | Shoes | 71 | | Fort Robinson | 25 | I E S C | 72 | | Trains | 26 | Man On White Horse | 73 | | Model T Ford | 29 | Nebr. to Cal | 74 | | Leaving Home | 30 | Music | 75 | | Ray Magnuson | 31 | Rotary | 76 | | Wedding Day | 33 | Turkey 1982 | 78 | | Depression | 35 | Turkey Revisited | 79 | | Barbed Wire | 36 | Changed Odors | 80 | | Dry Pants | 37 | Communications | 80 | | Where Does It Come | 38 | Reunion | 81 | | Sumner | 39 | Belief | 82 | | Putting Up Hay | 40 | Know What You Want | 83 | | Hay Sweep | 41 | It Works | 84 | | Saddle Horses | 42 | It Works Again | 85 | | Livestock Sales | 43 | Flood Control | 86 | | Leaving The Ranch | 44 | Vintage House | 87 | | University 1932 | 44 | Alcalde | 87 | | CCC Camp Days | 45 | Finale | 88 | | Superintendent CCC | 47 | | |

|  | | | Page Image | |

MY PARENTS

GUSTAV FRIEDRICH METZGER

On November 19, 1872, Gottlob & Louise Metzger of

Herrenberg, Germany, announced the birth of a son. They named

him Gustav Friedrich Metzger. This son was the third child

in the family of 7 girls and 3 boys. In 1880 the family

emigrated to the United States. The third son went by the

name of Fritz for much of his life. Fritz was also known by

his neighbors and friends as Fred G. Metzger, Fred Metzger

became my father, and was to set an example of honesty, thrift

and integrity that I have tried to live up to.

The Metzger family settled in Eastern Nebraska at

Tecumseh. They were farmers, and Fred, being the oldest son,

was given responsibility at a very early age. He worked more

than he went to school when he was young, and did not go

beyond the fourth grade, but he was a good student and read

a great deal, seldom a day would pass that he didn't read

from the Bible. He took several magazines dealing with

agriculture, animal breeding, and horse training. He was

usually up to date on events in his community and the

United States.

I never really felt close to my father. He was a

sensitive person, but showed very little emotion. I saw him

cry only once, and that was when he received the news of his

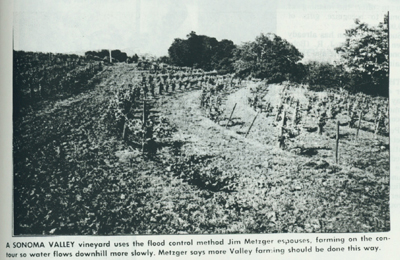

father's death on July 20, 1913. We all went to the

funeral, which meant a train ride across Nebraska.

Lawrence, my brother, was four years old and I was six. I

remember the house where my grandparents lived, and I can

still see the two sleek black horses hitched to the black

hearse that took the body to the cemetery.

I remember Dad as being very strict. I suppose that

he spanked me at some time, but I do not remember receiving a

spanking. I do remember, that he would slap my hand at the

dinner table, if I reached for something, he would just say,

"Someone will pass it to you." I never heard him speak an

unkind word to my mother. I have heard him say that his wife

would not have to work in the field, and then have to do her

house work. That meant nothing to me at the time, but I now

realize that he came from a society where field work was

expected of women.

Dad was an impressive person, standing 6 feet tall, and

weighing 225 lbs; in recent years he led with his belt

buckle when he walked down the street. He remained on the

ranch until he was past 70, and missed very few days of

work.

|  | | | Page Image | |

I do not remember Dad going to a doctor, his health

seemed always to be good. He died at the age of 88, from

prostate complications.

Fred Metzger was a conservative person when it came to

finances. He kept a perfect set of books, and was treasurer

for the school. I suppose he could be called a workaholic,

it was not uncommon for him to say on Monday morning at the

breakfast table, "This is Monday, tomorrow is Tuesday, the

next day is Wednesday, the week is half gone and nothing

done yet." I grew up with the feeling that I always must be

doing something productive, and I suppose that this is why

I am also a workaholic.

Fred's father was an officer in the German Army, under

the Kaiser. He came to America because he didn't want his

own sons to have to serve in the army. He was an

alcoholic, and Dad would have to go to the bar, late at

night, and bring him home drunk. It made such an impression

on him that he swore never to take a drink, and as far as I

know, he never did, nor did he smoke.

When I was very young, he promised me a gold watch when

I reached the age of 21, if I did not drink or smoke. I

received the gold watch, as did my two brothers. In later

years we all slipped a little, I like a glass of wine or

beer once in a while, and both my brothers smoked at one

time.

BESSIE GRACE PLATT

Bessie Grace Platt was born March 15, 1986 [sic], on a farm

north east of Crab Orchard, Nebraska. She was the middle

daughter in a family of five girls. James and Sarah Platt,

her parents, lived on the farm until the family was grown,

and then moved into Crab Orchard, where Jim Platt ran a

a grocery store. My early memory of my grandparents,

were visits to Crab Orchard at Christmas time when I was

not more than 5 or 6 years old.

My mother was a quiet, patient lady. Life must have

been difficult for her, she came from a family that was very

close. She married at the age of 19 and two years later

moved to a homestead in Western Nebraska, a wind swept, flat

plains country, very unlike the area in Eastern Nebraska

where she grew up. The closest neighbor was more than a

mile away, and not even in sight, and since I was born only

a month after they arrived, it would have been difficult for

her to visit anyone.

|  | | | Page Image | |

She told stories of helping the dog kill a rattle-

snake, and of chasing a coyote from the yard with a broom.

I once heard her say that homesickness was a real sickness

for her. I always felt closer to my Mother than I did to my

Father. I could always talk to her when I had problems. I

like to think that I inherited her ability as a peacemaker

and a sympathetic listener. I will always remember a

statement she made to me, when I was critical of some one.

"Just remember that the faults you see in others, may be

your own."

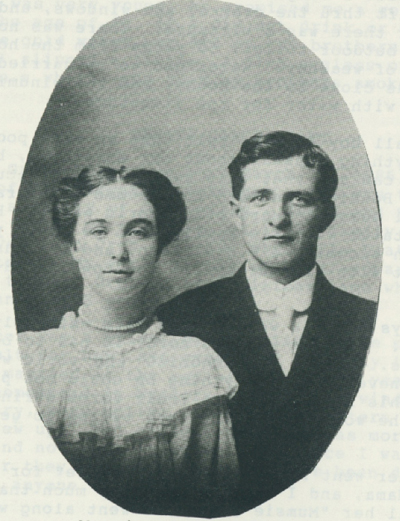

FRED AND BESSIE METZGER

Fred and Bessie were married in Johnson, County,

Nebraska, Aug. 12, 1905. They came to Crawford in March

of 1907. Fred had his homestead permit, but found a place

to buy, that was about 5 miles north west of Crawford. A

family by the name of Wolff had taken this property as a

homestead, but relinquished his rights to the Metzgers.

The 640 acres had a log barn, a frame house, and three

small sheds. There are pictures in the family, showing this

property without a single tree. As a boy I remember that

snow could sift thru the cracks, and windows, and cover my

bed when ever there was a blizzard. There was no indoor

plumbing; an outdoor toilet, 50 yards from the house served

in all kinds of weather. Water had to be carried from the

well which was close to the house, and the windmill kept the

tanks filled with water for the livestock.

As a small boy I never felt that we were poor, or that

there was anything unusual about our existence, but as I

look back, I can see that this was a very difficult time

for Fred and Bessie. Dad did not become a naturalized

citizen until several years after World War I. He came to

the United States with his family when he was 8 years old.

He delayed in becoming a U.S.citizen [sic], and it caused him

embarrassment with his neighbors, who considered him a

"German".

He always did his work on the farm extremely well, it

was his life. When he planted corn, it had to be in

straight rows. He was an economist the world will never

hear of; he never bought anything he could not pay for with

cash. When his neighbors lost their farms during the

depression, he would say, "They are trying to get big too

fast."

My mother went by the name of "Mumsie" for years. We

called her Mama, and I disliked that so much that I was the

first to call her "Mumsie", and Dad went along with it, and

from that time she was no longer "Mama".

|  | | | Page Image | |

Living conditions were difficult for Mumsie, she had to

pump and carry all the water that was needed for cooking and

washing. Food could be kept cool only in a cave, but it was

hard to keep things from spoiling. She was afraid to let

Lawrence and me get very far from the house when we were

small, for fear of snakes.

Dad raised horses, and sold many matched teams for farm

work. I have a series of books that are dated in the early

1900's that give instructions for training horses. I

learned to read these books at a very early age, and by the

time I was 8, Dad would let me drive a team in the field if

he was close by. I drove my first 4 horse team when I was

12 years old.

When Dad bought the second car, which was another Model

T Ford, the folks made a trip to Crab Orchard. I was 14

years old, and they left me to take care of the ranch. They

were gone three weeks, which seemed endless to me. Dad had

converted the old car to a pickup, by cutting the back seat

off and building a truck bed. I used the pickup to haul

feed and supplies on the ranch, and to Crawford, to pickup

groceries and mail.

| Bessie

Born 1886

Died 1973 | Fred

Born 1872

Died 1960 | Married August 12, 1905 |

|  | | | Page Image | |

MY BROTHERS

LAWRENCE & ERNEST

I was born April 1, 1907, and on October 25, 1908

Lawrence came into this world, and we were close enough in

age for us to have many common experiences. Ernest was born

November 27, 1912, more than five years later, and although

he went to the same one room grade school and the same high

school, our activities and interests seldom were the same.

We lived a mile and three quarters from school, and

occasionally Dad would take us if it were too cold or

stormy to walk, but most of the time we walked. It was

common for a child, when six years of age to begin school,

but our parents delayed my start until Lawrence and I could

go together. Our first day of school was in September

1914, and I was then past seven but Lawrence hadn't yet

reached his sixth birthday.

School seemed to be difficult for Lawrence, I remember

his being exhausted when we reached home at night. After

our chores were done, and supper over, we had an hour of

home work to do, but he had a difficult time staying

awake long enough to finish his work. Lawrence graduated

from High School, and graduated from Colorado University at

Fort Collins, as a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, (DVM).

It was not until he became a Veterinarian, that his illness

was diagnosed, and he did it himself. He had suffered with

Undulant Fever from early childhood. Lawrence had a very

successful practice in Northern Colorado, for over 40 years,

he was active on the Colorado Sate Board of Examiners, for

many years. Lawrence and Eileen were married in 1938 and

lived in Boulder. We saw them often when we lived in

Longmont from 1945 to 1955.

I feel some times as if I must be a member of another

generation from that of Ernie. He was five and one-half

years younger than I, but other than having the same

parents, our interests and activities were seldom the same.

I graduated from high school in 1924, Lawrence in 1927 and

Ernie in 1931. In 1927 I entered the University of

Nebraska, and Verna and I were married in 1928. With the

exceptions of short visits, I never returned to Crawford.

Ernie later graduated from Nebraska Wesleyan, attended

seminary, and became a Navy Chaplain. He served 30 years

and retired with the rank of Captain. He and Melva were

married in 1940. Verna and I visited them when his

assignments were in the United States, and we keep in touch

regularly thru the Metzger Robin letter and by telephone,

but the closest we were to them overseas was when we flew

over Germany in 1955 on our way to Turkey.

|  | | | Page Image | |

The transportation that Lawrence and I used when we

went to High School was much the same, but not until after

Dad bought his second car, and made a pickup out of the

first one, was an automobile used for transportation to

school. Ernie rode horseback also, but by that time milk

was being delivered regularly to the ice cream factory, and

delivery had to be made early in the morning when Ernie went

to School.

| The three Metzger boys, taken in 1914. This was

Lawrence's and my first store made suit. Mumsie made most

of our clothes before this time. Ernie eventually inherited

them. I never ask him how he felt about this. |

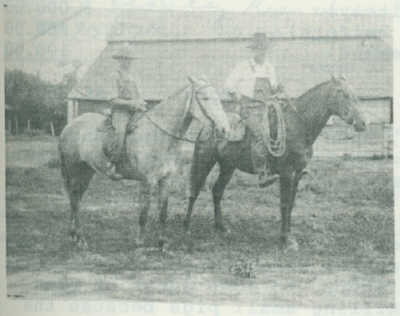

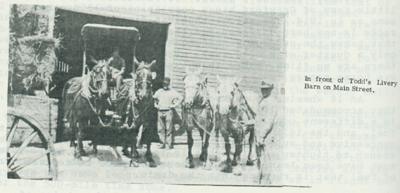

| This team of matched grays was typical of the horses

Dad raised. It was the first team I ever drove. The lad

in the picture is Ernie. Dad started his sons at an early

age. We were driving teams in the field as young as eight,

and he always worked along beside us with another team. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

COUNTRY SCHOOL

My introduction to formal education was in a one room

country school. It was 1.75 miles from home and there were

very few days that my brother and I didn't walk this

distance. Occasionally on stormy days Dad would hitch

old Charley to the buggy, and take us.

I remember one day in September when the temperature

was above 90 degrees F, and one winter day when it was 40

below zero. I was 7 years old and my brother 6, so this was

in 1914. The only early record I have is a souvenir from my

first teacher, Cora Sowers, dated 1914.

The 1.75 miles to the school was the longest mile

and three quarters I ever saw. Lawrence and I tried every

device, and every method possible to break the monotony of

this walk. We would take the shortest route as often as

possible by crawling over fences and walking thru fields.

This method was frowned upon by the neighbors, because we

broke down their fences and sometimes damaged young crops.

Mumsie did not like it, because it meant torn clothes

that she had to mend.

We devised methods of travel that helped time pass.

If we could ride a stick horse, it seemed to us to shorten

the distance. The most useful to us was a machine that we

make ourselves. This machine consisted of a small wheel

about 12 inches in diameter, we would put a small 3 inch

board on each side of the wheel, put a half inch bolt thru

the boards and the wheel. The bolt would serve as an axle.

The boards were fastened together at the top, about six

feet from the wheel, so this served as a wheelbarrow.

The use of the wheel kept our minds occupied, and time

seemed to pass more rapidly. To make it useful we would put

a nail in the board about half way from the handle to the

wheel. This was a machine to carry our lunch pails. When the

ground was smooth it worked fine, but when the ground was

frozen, where the cattle had walked in the mud, it was a

disaster. Mumsie made sandwiches, some with jam or jelly,

or perhaps we would have a small jar of stewed fruit, and

when we arrived at school it was hard to tell just what we had

for lunch. It wasn't soup, but it looked like it.

It was some time before Mumsie found out what happened.

There was dried jelly and fruit stuck to the pail, and when

she packed our lunch the next day she would have to give

the pail a good cleaning.

|  | | | Page Image | |

As far as I know, the one room school house is a thing

of the past. Our one room school, was Valley Star School,

District No. 28. Dawes County, Nebraska. The one room was

about 30 feet wide and 60 feet long, and contained the

material that the teacher needed to teach the first eight

grades.

We were a motley bunch of youngsters, we ranged in ages

from 6 to 14 years. The 14 year old girl, Maude Dahlheimer,

considered herself a mature lady. The little 6 years old

lad that didn't make it to the privy in time, and went all

day with wet pants, considered him self an outcast. I

often wonder how we appeared to the County Superintendent,

who visited us twice a year to inspect our work. I am sure

that the teacher knew when she was to coming, because we

would get instructions to put on our best manners. We often

worked very hard on some project in order to have it

completed in time for inspection.

I can still see the two rows of seats, that extended

from the platform where the teacher sat, to the back of the

room. There was the potbelly stove that was located in

the center of the room, the pail of water with the one

dipper that every one used. There was a line of clothes hook

that stretched across the back of the room, with a name

above every one of them, and there was the blackboard in the

front of the room with a crack down the middle.

The teacher rang the bell at 9:00 o'clock, and we would

be considered tardy if we were not in our seat within five

minutes. If I was late getting in my seat, I could miss the

first recess, and be required to clean the black board,

and empty the waste paper baskets.

I remember being tardy only once, and it was very

embarrassing, I was the laughing stock of all my friends,

Mumsie had sewed some buttons on my pants and I couldn't

keep them buttoned. I thought if I got there a little late

that no one would notice.

My memories of country school have always been good.

My problems with grammar and spelling have followed me all

my life, but I don't think it was the teachers fault.

The girl I married was an English teacher, and I am still

going to her for help in spelling or grammar.

|  | | | Page Image | |

| Cora Sowers was Lawrence's and my first teacher. I

remember her as a very soft spoken person, who taught me

the multiplication tables. |

Valley Star School

District No. 28

Dawes County, Nebraska

1914-1915

CORA L. SOWERS, Teacher

PUPILS- Bert Lewis

- James Metzger

- Lawrence Metzger

- Jennings Raben

- Frank Dahlheimer

- Julia Hunter

- Florence Leonard

- Catherine Raben

- Eeva Dahlheimer

- Maude Dahlheimer

SCHOOL BOARD- P. L. Raben, Dir.

- T. J. Hunter, Mod.

- F. Metzger, Treasurer

|  | | | Page Image | |

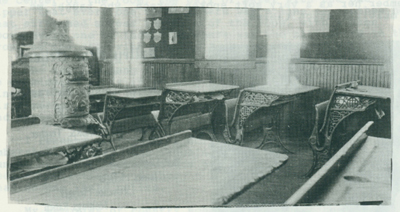

| VALLEY STAR SCHOOL: District No. 28, Dawes County

Nebraska. The addition of the cloak room on the front, was

made in later years. The overshoes and winter coats as well

as the coal scuttle could be kept out of the school room.

The water pail and drinking cup, (used by all) was kept her

until it became so cold that the the [sic] water would freeze. |

| The school room where two pupils could sit at a desk.

I never had to share a desk, but some of the smaller

students did. In the winter time it was too hot to sit by

the stove and too cold to sit at the back of the room. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

THE ONE ROOM SCHOOL

There were two of us in my class for the years that I

was in country school, Catherine Raben and myself. When we

were called on to recite our lessons, the teacher would call

us to the front of the room, and we would sit on chairs

facing her as she sat at her desk. If I was poorly prepared,

or had forgotten some of that day's assignment, I felt as if I

were being called before a judge for some traffic violation.

Normally, the teacher's questions began with our

assignment that day, but it could be on something we should

have remembered from the day before. Some times she would ask

for illustrations on the black board. Arithmetic, English

and geography were often assignments that called for black-

board work. I liked mathematics and geography but English

and grammar gave me a headache, and it remains one of my

problems as I write the story of my life.

The early grades were not hard for me, but I found the

eighth grade more difficult. I have decided that the

students in the lower grades had the advantage of hearing

the higher grades recite their lessons. It was a help for

those who followed, but by the time I got to the eighth

grade, I was on my own.

One of the highlights of my time in the country school

were the two recess periods, we had 15 minutes in morning

about 10 o'clock and another in the afternoon at 2:30. We

usually played outside if the weather permitted, snow on

the ground meant we could play fox and geese, or snow

ball. The snowball fights often ended in some of the small

children getting hit hard enough to call for intervention

from the teacher. We played baseball in the spring when it

was warm, and this included both girls and boys.

The school house was a cold place in the winter. We

were always dressed well, long johns and heavy undershirts.

The stove in the middle of the room was usually fired with

wood or coal that we would carry in from a shed close by.

The most difficult time to stay in school was when spring

came. It was hard to stay inside and study when the birds

were singing and flowers blooming.

To get to school during the winter could be a problem

if the snow was deep, and to get caught at school in a

blizzard was a worry for parents. There was little warning

if there was a blizzard on the way. The weather could be

nice when left home in the morning and be a raging storm by

the time school was out.

|  | | | Page Image | |

We had good roads and fences to follow when it was

stormy, there were many stories in homesteading days when

children got lost in blizzards. There was only one time

that the storm came so quickly that we were picked up at the

school. The only warning we had, that a blizzard was on

the way, came over the wires from the Burlington R.R. A

call would be sent out over the country lines that we could

expect a storm to reach us soon.

The nine months of school were over on the last day of

May. We would often have a picnic, and the parents would

celebrate with us. This last day could be a big affair,

parents and relatives would arrive at the school at about

ten o'clock. They would arrive by wagon, buggy, or horseback

and some would walk. We had only a small hitch rack for

horses, but there would be teams tied to wagons and fence

posts that were close by.

When it came time to start the activities, everyone

would go into the school house. The teacher would speak for

a few minutes, she would proudly tell of the accomplishments

of her students during the past year. There would be high

praise for the students who had excelled in their grades

for the year. I don't remember receiving any awards, except

in mathematics.

If it were nice weather we would then gather outside

and share our lunches. If it were bad weather we would push

the desks back against the wall and set up some plank tables

where we spread our lunches. If it was warm weather there

was always someone who brought a freezer of home made ice

cream, and there was always lots of cakes and cookies.

The last day of school that I remember best, was on the

31st day of May 1917. It was the only time I remember

seeing snow in May. It had snowed enough, that Dad took the

sleigh, saying "I never have gone sleigh riding in May,

this will be the time." When we came home most of the snow

was gone and we rode at the side to keep the sleigh runners

on grass, we called our sleigh a grass schooner.

|  | | | Page Image | |

PRAIRIE FIRES

It hasn't rained for a month. The temperature ranges

from 65 degrees in the morning to 105 in the afternoon. It

seems that every day about 2:00 O'clock the wind blows from

the south, and it feels as if it were blowing over a hot stove.

Everything is dry, and the grain fields that are not yet

harvested are so ripe that a heavy wind shatters some of

the grain on the ground. The only time it can be cut is

in the early morning, or we lose half the crop.

Dad is cutting grain on the east eighty, and starts

cutting early in the morning about sunup. I will take a

fresh four-horse team to him about 9:00 O'clock so that he

does not have to rest the team. I feel that I am grown up

at age 10, because I can go to the barn, get the collar that

fits each horse and lead them to the field. Dad will then

remove the harness from the team he is working and put it on

the fresh team that I bring. The harness will fit the team

I have brought, but each horse has to have a collar that is

specially fit, in order not to damage the animal.

It is the middle of August, 1917, at 10.00 O'clock

in the morning, I have returned with the team that Dad used

earlier. I take them to the water tank, then to the barn

and feed them. It seems to me that the day is hotter than

usual. By 11:00 O'clock the wind begins to blow and Dad

comes home early, he says he is losing too much grain

because it is so dry.

When I was a boy, dinner came at noon, and then a nap.

We had just finished dinner and the telephone began to

ring. It wasn't the regular long and short combination that

calls some one to the phone, it was a series of short quick

rings that lasted for only a few seconds. This was an

emergency call and every one would get to the phone as fast

possible.

Dad went to the phone, without saying a word to any one

on the line, he quickly banged the receiver down, turned and

said. " A fire on Dawes Forbes' place. The fire has jumped

the fire guard." That means only one thing, the fire is

heading for our place.

Dad grabbed his hat and gloves, and turned to me and

motioned for me to come with him. We went to the barn, took

the four horses he had been using, hitched one team to the

wagon. I took the other team, rode one and led the other

horse.

|  | | | Page Image | |

We loaded two barrels on the wagon, drove to the water tank,

and filled the barrels with water. We then took a walking

plow, a roll of sacks and started for the fire. When we

left the house, we could see a little smoke in the south

west, it didn't look to be much of a fire, but when we came

to the top of the hill we could see that we were in trouble.

The fire was definitely headed for our house.

It had been fully an hour since the heavily loaded

freight train, headed for Sheridan, Wyoming, had passed by.

I could only imagine what had happened. The Fireman was

stoking a big fire to keep up a head of steam. The huffing

and puffing locomotive had belched hot cinders with the

smoke. It had started five fires within the mile. The

fire guards had stopped all but one of them. That one had

jumped the guards and was headed for our buildings.

We were not the first to get to the fire, two

neighbors had been there ahead of us. Harold Shipman and

John Dodd were plowing another fire guard several hundred

yards ahead of the fire. They had successfully shut off the

part that was headed for our house. We were probably

safe, but Harold's wheat field had not fared so well, thirty

acres of shocked grain were already lost.

The grass and stubble was short, this meant that we

could get close enough to the fire without getting caught

with the team and wagon. I drove as closely as I could to

the fire line and neighbors,who [sic] had come by horse back and

buggy, were able to take the gunny sacks, soak them in water

from the barrels and hit the fire with the wet sacks. It is

amazing how well this could control a fire.

I was under orders from Dad to stay on the wagon, and

keep a good distance from the fire. He hitched his team to

a plow and joined the others in plowing more fire guards.

I drove as close to the fire as I dared, while the men

flung the soaked sacks to snuff our the fire. In order not

to get caught with the flames, they worked in from the side

and directed the fire to an area where the men and teams

were plowing the guards, turning the prairie land into

brown strips of freshly turned soil.

With grass that is no more than four to six inches

tall, the fire line looked like a red fringe to a large,

black rug that was being unrolled. The fire is swept

along by the wind as fast as a horse could walk. It was

only four or five miles per hour, but if you owned hay

stacks, grain fields or farm buildings in its path, that

seemed much too fast. One neighbor lost a wheat field that

had the grain in the shock. Another lost a stack of hay.

We escaped with only burned grazing land.

|  | | | Page Image | |

Several miles from this fire there was another. Little

damage was done because one of the neighbors, Walter Heath,

was able to stop it from spreading by plowing a guard around

the burned area. Walter didn't come home when the fire was

out. They found him sitting up against the wagon wheel.

The team came home and were standing by the barn, still

hitched to the plow. Walter had died of a heart attack.

It would appear that once a prairie fire was put out

that it would be safe for the fighters to go home, but this

was not the case. Some one had to stay on the job, perhaps

for several days. Hot weather in Western Nebraska would breed

small twisters or whirl winds. Some times dust and ash would

get caught in one of these twisters, and be lifted a 100 feet

in the air. At the same time unburned weeds or cow chips

would get caught in the up draft and be rolled along the

ground and start another fire. Cow chips could hold fire

for several days.

I was fascinated by the burned areas, I would walk

over the area to see what took place. Only a few birds ever

lost their lives. Most of the meadow lark nests would be

empty. Snakes often didn't find a place to hide, and would

die. Some times a turtle would be found dead, but most

often they escaped the heat. Baby rabbits could be found

with singed bodies killed by fire or smoke.

The wooden fence posts would often be burned off at

ground level and would need to be replaced. If rain fell in

the fall the area would green pasture again. If there

was no rain it remained a black carpet all winter, if not

covered by snow.

I never hear of fires being started by trains any

more. Lightening will sometimes start one, but the

prairie fire in the ranch country of Nebraska, Wyoming

and Colorado is still to be feared.

|  | | | Page Image | |

| William M. Forbes, our teacher in 1917-1918, was our

authority on Russia. The seed corn project created a lot of

interest in the community. It was my first introduction to

the world that existed outside the boundaries of Dawes,

County, Nebraska. |

Valley Star School

DISTRICT NO. 28

Crawford, Nebraska

December 25, 1917

William M. Forbes,

Teacher

School Officers- P. L. Raben Director

- F. G. Metzger Treasurer

- T. G. Hunter Moderator

PUPILS- Edwin Ostermeyer

- Alma Ostermeyer

- Alfred Ostermeyer

- William Ostermeyer

- Ralph Ostermeyer

- Martha Ostermeyer

- Maude Dahlheimer

- Catherine Raben

- Jennings Raben

- Elmer Raben

- James Metzger

- Lawrence Metzger

|  | | | Page Image | |

ODESSA

ARA FOR JDC ODESSA, I will always remember ARA FOR JDC,

(AMERICAN RELIEF ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH DISTRIBUTION

COMMITTEE). For 75 years this has been in my mind. The

Russian Revolution of the 1990's brings memories of the

Russian Revolution of 1917. The one in 1917 was important

to me because I played a part in a project that was designed

to help the food shortage. The total deaths from starvation

was never known, some estimates placed it at a hundred

thousand.

Alan Moorehead's book; THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION describes

in detail the plight of the Russian people during 1916 and

1917. "The winter of 1916-1917 was particularly severe--at

one stage no less than 1200 locomotives burst their frozen

pipes--making it impossible for adequate food distribution.

In Odessa, people had to wait two days in line to get a

little cooking oil. In Petrograd and Moscow bread lines

formed through out the freezing night."

By the time the fighting had ended, all the seed grains

had been eaten, and there was no seed available for planting

the 1918 crop.

In 1917 my father received a request for seed corn,

from the American Relief Association for Jewish Distribution

Committee. Russia needed seed corn that came from a land

with climate similar to that of the Ukraine. Western

Nebraska: Elevation 4000 feet above sea level: annual

rainfall of 20-24 inches, and lying between the 40th. and

50th. parallel, with a 90 to 100-day growing season, met

these requirements.

As Dad picked the corn, ear by ear, and threw them

in the wagon, he carefully selected the best ears and threw

them in the front of the load. When he unloaded, he put the

selected ears in a separate bin. He gathered his own seed

corn in this manner, but this year it would include 200

bushels of ear corn that would be shipped to Odessa [sic] Russia.

By December all the corn was harvested, and special

instructions were given for shipment. The American Relief

Association would pay for the corn, the price would be

double that received for livestock feed. I think the price

paid was $.50 per bushel.

|  | | | Page Image | |

Each ear of corn was to be carefully wrapped in paper

to protect if from salty air while in shipment. We used many

Montgomery Ward catalogues and newspapers. It was then

packed in burlap bags, each bag was sewed shut and marked

ARA FOR JDC ODESSA. I was given the task of lettering each

bag, I stretched the bags out on the floor, and placed a

stencil over each bag, and carefully filled in each letter

with black paint. There were 100 bags, each holding two

bushels of ear corn.

We prepared the corn for shipment in December. It was

very cold so we did the work in the house. Mumsie cleared

the kitchen table and we set up sawhorses with planks as

work benches. This became a family project for my parents,

my younger brother and myself. I was 10 year old, I felt

VERY IMPORTANT and I made sure the bags were lettered

properly.(ARA FOR JDC, ODESSA),

The project was the talk of the neighborhood. Our

teacher, William Forbes, lost no time in getting a world map

on the wall of our one room school house. He showed us where

Russia was located on the globe, he read from the encyclopedia

and told us about the people, the country and the Czar.

The Russian Revolution of the 1990's is different but

there are many similarities. Will there be food shortages?

Will people starve as they did in 1917? Will there be a

civil war? What will the new government be?

As events unfold in the 1990s we will see them

happen, they will come to us in the living rooms. We will

have many opinions from people who know a great deal about

the country and its people.

In 1917 we had no radio, no television, our information

came to us from the local paper that we received weekly. We

always had the Nebraska Farmer, an agricultural paper that

was concerned with local agricultural matters in the state

and nation but little was ever said about the world.

The little one room school house, in 1917 boasted of

fourteen students, grades one thru eight. The 21 year old

year old teacher with his maps, the globe and the monthly

Current Events paper was our source of information. HE was

our expert.

|  | | | Page Image | |

FOOD

The task of obtaining adequate food for each day is not

a problem for most of us, we go to the super market and

everything we need for a balanced diet is on the shelf.

Today refrigeration, transportation and well organized

distribution has made it possible, not only to get the

necessary food for survival, but to have special foods at

all seasons of the year.

How different it was 80 years ago. There was no

refrigeration, many perishable crops could be moved only a

short distance from where they were raised. The majority of

people had to provide all their own food and a little extra

for those who lived close enough to get it before it

spoiled.

To grow the food and process it, required much time,

and many skills. I learned many of these skills from my

parents. On the ranch, we raised our own meat, vegetables,

eggs and milk. We slaughtered and processed the meat. We

grew the crops that could be dried, canned, or stored in

caves. We bought only a few necessities, such as salt, sugar,

kerosene for lights, and wood or coal for cooking. We raised

wheat and had it ground into flour at the river mill, only a

few miles from home.

My father was an expert at butchering hogs and in

preserving the meat. He not only did it for his family, but

he often supervised the project for the neighbors. The

killing of a hog was a painless process for the animal, it

would be stunned with a heavy hammer, and with great skill, a

knife would sever an artery at a point where it forked,

between the jaw and the front legs. The blood was saved as

food for the chickens.

To clean and dress a hog required several operations.

Water was heated in a 55 gallon barrel; when it reached

the proper temperature, it would be lowered into the barrel

and held long enough in the hot water until the hair could

be scraped off. This was done with a scraper or large knife.

The carcass is then hung with head down and offal removed.

The liver and heart were quickly cooled, this would be the

meat we would have for supper. The carcass is allowed to

cool over night. It will then be cut into hams, sides for

bacon, and other cuts.

|  | | | Page Image | |

With no refrigeration the next operations must be

completed in a hurry. The hams are rubbed with saltpeter

(Potassium Nitrate), put in a smoke chamber, (smoke house),

for several days or even weeks. A wood fire, or ear corn,

would create enough smoke to produce a delicious cut of ham

or bacon.

When the remainder of the meat was cut, there would be

tenderloin, the back loin which is now served as pork chops

Often because of lack of refrigeration, much of the meat

was roasted and put in glass jars and sealed. Wonderful

roast pork could be preserved for the rest of the year.

The feet were well cleaned and pickled. The head became

head cheese. The remainder was ground, and made into link

sausage by cleaning the offal and stuffing it with ground

meat, and smoked with the hams and shoulders.

When Verna and I were living on the ranch in the 1930s

we butchered a beef more often than hogs. Verna would

preserve much of the beef by roasting and canning in glass

jars, which made the best roast beef I have ever eaten.

The farm flock of laying hens supplied the family with

meat and eggs. Eggs were traded at the local grocery store

for many items used in the kitchen. Mumsie was able to buy

materials for making clothes for us.

|  | | | Page Image | |

EGGS

"HELP! HELP! I can't get out!" I tried to go forward,

I tried to go backward, nothing seemed to work. I was

caught between the floor joists under the barn, and the hard

ground. My 5 year old brother Lawrence, was the only person

who knew where I was. I yelled at the top of my voice but

got no answer. I was scared. How was I ever going to get

out of this mess.

I suppose it was no longer than 10 minutes, but it

seemed like 10 days. I tried to crawl out of my clothes, but

I couldn't unhook my suspenders. I was crying and yelling,

and I finally got an answer from Lawrence. I didn't know

where he was, but he was soon pulling on my pant leg. He

unhooked my pants from a nail in the floor joist and gave me

enough freedom to wriggle backward and free myself.

Spring on the ranch brings calves, pigs, lambs,

kittens, colts and chickens. As for the chickens, the eggs

came first. My brother and I were hunting eggs. Mumsie was

the proud owner of a flock of prize Buff Orpingtons that

furnished her with eggs enough for the family table and a

surplus with which she purchased most of the groceries

that we needed.

The selection of the breeding stock was an important

process in maintaining a productive laying flock. Eggs were

collected for several weeks and then placed in an

incubator. In three weeks another laying flock was on the

way.

The chickens were allowed to run free at the ranch, and 1

eggs were not always laic in the proper nests in the chicken

house. In the spring, a brooding hen had her own idea as to

what was needed to raise young chicks, she would hide

her eggs under the feed bunks in the barn or even under

buildings. Lawrence and I could earn a little money if we

found eggs in hidden nests. We would be paid a penny an egg

for all we could collect.

Trying to find eggs is what got me in trouble. I was

under the barn and spotted a nest in the far corner. I

tried to crawl thru the same opening that the hen had been

using, but I didn't make it. Lawrence was a little smaller

than I and did get thru and found six eggs. We divided the

six cents.

Years later I looked under that old barn. That hole

as [sic] still there, but I didn't see any eggs.

|  | | | Page Image | |

NO CASH

I have heard that there is a lot of business conducted

in the United States by using the barter system. You can

trade commodities with out showing any record of a cash

transaction. I am told that millions of dollars are lost in

taxes, and that the IRS frowns on this type of business.

Business transactions, where no cash was used, were

common when I was a boy. It was not the intent to avoid

taxes, it was because there was no cash. Business conducted

by the barter system, could be for services or commodities.

My mother always planned to raise chickens for meat and

eggs, enough to supply our own food, and we always seemed to

have eggs to take to the grocery store and trade for other

produce. Eggs from the flock of laying hens, and cream and

butter from the cows we milked, were bartered for groceries

at Frank Lewis' grocery store. The list of things needed was

prepared by Mumsie, there was usually, salt, sugar, pepper,

baking powder and other items needed in cooking.

The eggs and butter were carried in a large basket,

which would then be used for groceries. The process of

obtaining the groceries always interested me. I would watch

Dad count the eggs, then watch Frank get each item from the

shelves as Dad read the list Mumsie had prepared. Some

times a shipment of oranges had been received and Dad would

select one for Mumsie, Lawrence, himself and me. Some times

Frank would give me a piece of chocolate candy. I was just

tall enough to stand on my toes and look over the counter,

and reach the candy.

When the groceries were in the basket, Dad would take a

small pencil from his pocket, scribble on a piece of paper,

Frank would do the same, Dad would say, "I owe you $1.50,"

Frank would then say, "I will put it on the books until

next time." I never did see any money change hands.

I think that my brother Lawrence is the only person who

will remember this next story. Dad, on one of his trips to

town, had a nice team of well matched grays, he was alone,

and carrying a large basket of eggs on his arm. As he

crossed the R.R. tracks a switch engine hit him. The engine

ran over his team and made kindling wood of his wagon. The

team had to be destroyed, they were so badly mangled. Dad

came out without a scratch. His clothes were completely

covered with egg yolks. He called Mumsie as quickly as

he could get to a phone so that she would know that he was

not hurt. He wanted to get the news to her before it got

to the party line.

|  | | | Page Image | |

RED SHIRT

It was not always easy to communicate with our

neighbors before 1914, we had a telephone before that date,

but some of the neighbors did not. One of them was a

bachelor who lived in a sod house that was only a little more

than a mile from where we lived. I never heard him called

anything but "Squeaky Johnson." Squeaky got his name from

his high pitched voice. He always made me feel as if he

were yelling at me. He was a good neighbor, and could always

be depended upon to help us when we needed him.

One of my mother's complaints, was, when some one

wanted to get in touch with Squeaky, they would call her.

It was not uncommon for her to stop her work, and walk more

than a mile to get the message to him. When I became old

enough, I must have been 5 or 6, she would write out the

message on a piece of paper and I would deliver it.

The little sod house where Squeaky lived was not one of

my favorite spots. During the summer he kept a large bull

snake around to keep the mice and rats from invading the sod

house. The bull snake was a welcome visitor; it also kept

the rattlesnakes away. I hated to go near when the snake

was around.

One July morning, Mumsie received a message to deliver.

She was making shirts for my brother Lawrence and me. She

had completed a bright red one for Lawrence, and I was to get

the next one. She didn't want to stop her work, so she asked

me to deliver the message, and to take Lawrence with me. I

was busy pounding nails in a box, trying to make a house for

our dog. I was unhappy and didn't want to take Lawrence

with me, he was not able to go as fast as I wanted to go, so

I went off and left him. As soon as I had delivered the

message I hurried home to get back to my work.

We had taken a short cut thru a wheat field, the wheat

was as high as my head, and it wasn't long before I lost sight

of Lawrence. I was mad, and didn't care that I had lost him.

As soon as I returned, I got back to my task of

building the dog house. Noon arrived, Dad came from the

field, and Mumsie called us to dinner. The first comment

from Dad was, "Where is Lawrence?" I said I didn't know. The

next question was directed to me. "James, didn't he go with

you to deliver the message to Squeaky?" It had been three

hours since I got back home. I didn't know where he was.

|  | | | Page Image | |

I would have been better off had I known. I was

scared, if Lawrence is lost I am in real trouble. Dad

leaped from the dining room table, went to the barn, saddle

his horse, mounted and pulled me up behind the saddle, and

told me to show the way we had gone. For an hour we crossed

and recrossed that wheat field. Suddenly, Dad stopped his

horse, right in front of us was a sobbing little 4 year boy

wearing a bright red shirt. Dad reached down and pulled him

up into the saddle with him. Not a word was spoken until

we reached the house. As we sat down to dinner, Lawrence,

between sobs, said, "Didn't you see my RED SHIRT"?

I never was punished for running off and leaving my

brother. I think my parents knew that I was badly scared.

Dad just said, "Don't run off and leave any one again." It

is painful to this day, for me to leave someone if I think

they may be lost, or have no way to get home.

| If this picture were in color the shirts would be red.

I am sure that when Lawrence outgrew his he would get

mine, so he would wear a red shirt for a long time. The

same would be true of the overalls. These overalls were

special, they had two buttons for each suspender. When I

got caught under the barn I couldn't get one of the buttons

unhooked. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

TRANSPORTATION TO SCHOOL

In May of 1920 I passed the county examinations that

permitted me to enter high school. In September I enrolled

in the high school in Crawford, Nebraska. It was about 4.5

miles from the ranch to the school. I rode a horse for the

4 years, and only on rare occasions would I be permitted to

use the car.

My father raised horses, and much of his income came

from selling teams of horses for farm work. He occasionally

would sell one that would be used on a single buggy or as a

saddle horse. Some times the horse would be partly trained,

and it was my task to do some of that early training.

I remember the name of every horse I rode. Many of

these horses were only half broke, and did not want to be

ridden. This meant some rough rides for me. The first

horse was Bob, a flea bitten sorrel, Bob always wanted to turn

and go home when he got to the bridge, As a small boy I used

to go as far as the bridge and then turn around.

There was Lucy, Betty, Smokey, Baldy, Dick. I remember

three of these horses better that the others, because they

occasionally left me sitting on the ground and I would have

to walk home.

Lucy hated automobiles and trains. In 1920 there were

only a few automobiles on the road, and when one of these

contraptions came along with flapping side curtains, she

would have a fit. She would turn in spite of anything I

did, and start for home. Usually the driver would stop,

turn off the engine, and let me pass. I would still have

to get as far from the car as possible.

There were two railroads in Crawford, and the tracks

crossed at the point I entered the city limits. The

engineers would take delight in blowing the whistle. Lucy

would jump and start to run. One time she just stuck her

head between her front legs and bucked me off, and I had

to walk all the way home.

Baldy hated dogs, and in the fall during fair time, the

Indians from the Rose Bud reservation, would camp along the

road where I crossed the river. The dogs around the camp

seemed to take delight in snapping at Baldy's heels. She

would kick at them, and occasionally hit one and send him

head over heels into the borrow pit at the side of the road.

The fair usually lasted 8 or 10 days, as time passed, the

number of dogs that bark at my horse, became fewer, and

the lines of dried meat got longer.

|  | | | Page Image | |

Smokey was a small, ugly horse, a dirty smokey [sic] color,

with a dark stripe down his back. My father would never

have had it on the ranch under normal conditions, but he had

hired an Indian from the reservation to help him harvest the

fall crops, and he had loaned him some money, that he couldn't

repay, and so gave Dad the horse. Smokey had a bad habit

of running away. I broke chin straps and bridle reins trying

to hold him, he would run for home and go right into the barn

if the door was open. Eventually I found a way to stop him,

I took a long shank curb bit, with a wire jaw strap, and

put an end to his running.

I rode to school in all kinds of weather, hot, cold,

snow or rain, but with proper clothes I could keep warm and

dry, Handling a horse in very cold weather could be

difficult, if it were below zero, 40 below is the coldest I

remember, great care had to be taken to get the frost out

of the bit. A bit with frost in it can take the skin off

a horse's tongue. The frost can be removed by putting

the bit in water or blowing on it, the moisture from the

breath was enough to take the frost out.

It was several years before I was permitted to drive

the car, and then it had to be for special occasions in my

senior year. The saddle horse was my transportation.

| This was the first horse I owned. Dad gave me the

gift when I was 8 years old, I named her "GERTIE". I looked

forward to the day when I could train her. One day an

evangelist came to the door and was explaining to Mumsie

that the world was sure to come to an end in about ten

years. My first thought was that I would have time to

train my horse. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

PEST CONTROL

Are you being eaten by bugs, lice, fleas, mice or rats?

Call the pest exterminator. He will bring his chemicals and

electrically powered machines and clean things up for you.

As late as 1932 we had no electrical equipment and very

few chemicals that could be of help. We had to invent

our own method of getting rid of the pests. If we

couldn't get rid of them, we just lived with them.

It seemed to me, when I was a boy, that my folks were

always fighting some kind of pest. Flies, bedbugs, fleas,

mice, mites, these were always a concern in the house. Lice

ticks, fleas, worms, were year around problems with cattle,

horses, hogs, chickens, cats and dogs. Grasshoppers, potato

bugs, and worms were eating up our garden and other crops

the minute we turned our backs.

The ordinary house fly, on the ranch where there were

cattle and horses, was the most common pest. We built fly

traps that caught them by the thousands. The traps were

made of ordinary window screen rolled into a cylinder with

cone shaped entrance at the bottom. Fly bait of food would

attract the flies, when they flew away, they would hit the

cone shaped part of the trap and crawl into a hole that the

could never find to get out of. Then there was sticky fly

paper of various kinds. The ribbon of sticky paper that

hung from the ceiling, or the large flat piece of paper wit

glue that was an attraction for flies and bugs.

Bedbugs, ticks or fleas were not common if care was

taken to keep things clean. The problem could arise at

harvest time when extra help was hired. Mumsie made sure

that some of the clothing would be left outside, but that

didn't always work. When there was evidence that some of

these pests might be present, she would close up the house

and put a pan of sulphur [sic] on the floor and light a match

to it. The fumes would kill every living thing in the

house. When the sulphur [sic] burned out, she would open up the

house, and air it out. When winter came, mice could always

find a way into the house.

The worms and bugs always seemed to get to the garden

before we did. The tobacco worms on the tomato vines, or

the potato bug on the potatoes. The chemical that we used

was called PARIS GREEN, a bright green powder, made by

mixing sodium arsenic with copper sulfate and acetic acid.

We would put a small amount of the mixture with water in a

pail, and walk down the potato row and sprinkle the mixture

on the vines. If we did not use the poison, we took a small

can with some kerosene in it and picked the bugs and worms

off the vine and threw them into the kerosene.

|  | | | Page Image | |

The farm animals were always needing care. Lice were

common in winter, when there were long winter coats of hair

on the horses and cattle. To keep the lice under control we

would wrap a post in the corral with rags soaked in kerosene

or motor oil. The cattle, horses and hogs took care of them

selves by rubbing against the oily rags. Occasionally we

would mix kerosene and oil and rub it on the animal.

Lice and mites on chickens were treated by painting roosts

and nests with a creosote mixture and put wood ashes in

the dusting pans.

Mice in grain bins was always a problem. We had cats

around that helped control the mice. One of our neighbor

kept a bull snake during the summer months. Cats that had

kittens in winter could keep them alive. In summer I

suspected the bull snake was getting them.

We kept a few cats around the barns, if we fed them

a little milk when we milked the cows, they never seemed to

need any other food, so we were seldom bothered with mice in

our feed bins.

| The sod house was hard to keep free of pests. Bugs and

flies always found their way thru the windows and doors.

Mice were always a problem. "Squeaky Johnson's" sod house

looked much like this one. He kept a cat during the winter

that would take care of the mice, and in the summer time

his pet bull snake was very effective. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

HIGH SCHOOL

My high school years were not the happiest years of my

life. From a one room country school, where we seldom had

more than 10 or 12 students, to a high school that had 140

students with four or five teachers was to be a difficult

adjustment for a 13 year old country kid. Most of my high

school class mates had been together thru the first eight

grades, and had many friends. There were only two of us

from my school. It appeared to me that all were dressed

better than I, and my self esteem was about as low as it

could get. I thought I was the country hick. It was to be

many years before I could rid myself of that feeling.

Every morning before I left home I had to care for the

horses and cattle. As soon as I was finished with my chores

I would grab my books, hurry to the barn, saddle my horse

and ride the four and one half miles to the barn where I

kept my horse. I would make a run for school before the

bell rang at 9:00 o'clock, At 3:30 p.m. I would reverse the

process, and hope to get home before it became dark.

My mother would have supper ready as soon as we were

thru with our chores. The regular diet would be meat,

potatoes and gravy, with homemade bread, which we washed

down with lots of cold milk. The family always ate together

and Dad usually wanted to know what we had learned that day.

Home work would take an hour or two. I studied at the

dining room table, by the light of a kerosene light. It was

a great help when we were able to get a gasoline light that

hung from the wall and lighted the entire room.

Bed time came at 8:00 o'clock, and we were up the next

morning at 5:30. I expected to do this five days a week,

and Saturday meant extra work to haul enough feed to last

for the following week.

I looked thru my records and found the transcript of

grades that were sent to the University of Nebraska when I

matriculated in the fall of 1927. The 32 credits required

to graduate included English, Latin, chemistry, physics and

mathematics. The electives included manual training, and

typing. English and Latin were difficult for me. I took

Latin the second time, and then just got passing grades. I

liked manual training, Dad had taught me to use wood working

tools, and I could make the other students look like

amateurs. This was the only time that I really felt equal

to my peers. I graduated with an average grade of 80.

I liked manual training the best, but the typing class

was to prove the most valuable course in High School.

|  | | | Page Image | |

I can only imagine what my college work would have been

with out a typewriter, I established several USDA flood

control projects while with the CCC camp and Soil

Conservation Service. I often made preliminary surveys

with out clerical help. There were reports while on

assignment in foreign countries, where clerical help was

not available. A shortage of technical staff and language

problems made it necessary to write my own reports.

I have to confess, that even I had a hard time reading

my hand writing when it got cold. My typewriter made it

possible for others to read what I wrote. My spelling has

improved, when I wrote by hand I might be able to make A

look like an E or an F, and if it were type written it had

better be correct.

I worked all summer in 1924 to save $60.00, and bought

a Remington portable typewriter. In 1928 I married an

English and typing teacher, who taught the same typing class

that I had taken 4 years earlier. You can understand why

I was especially careful when I wrote love letters to her.

Verna is still of special help when I do this writing.

How can I look up a word in the dictionary, or even get my

computer to spell, if I can't even get the first two letters

right? I have just ask her how to spell curriculum, I can't

find it under CA or CO. she says, "look under CU."

Participation in extra curricular activities while in

High School was difficult for me. It was necessary for me to

work mornings and evenings at home. I did get my parents to

let me play foot ball my senior year, but this was not very

successful, the Crawford team won the western Nebraska

championship in 1923, the year that I played, but I was not

experienced and played on the second team most of the time.

I took the hard hits from the backfield of the first team.

I had one experience that I will probably never forget.

Working in the manual training class was a friend that liked

caramel candy, one day he gave me a piece, I liked it so well

that I gave him a nickel to get me some, he would give it to

me at the next manual training class. He never did come back

to class, and I lost a nickel. I don't know whether it was

because I lost the nickel, or that I didn't get the caramel

candy that made me remember it all these years.

I gradated in June 1924, I did have an opportunity to

show some of my skills, the seniors put on a play the week

of graduation. A request was made for members of the class

to provide some entertainment between acts. I volunteered to

play my banjo and harmonica. This was a novelty act that

was new to the audience, and I got a good hand. This act

brought me a lot of attention. I guess I needed this to

satisfy my ego.

|  | | | Page Image | |

DEEP SNOW

It was April 1922, and the day dawned bright and clear.

It was like many other April mornings in Western Nebraska. It

had been warmer than usual for April and much of the ground

preparation for planting, was finished. This year Dad is

seeding alfalfa with the oat crop. The oats will be

harvested in August and the alfalfa would continue to grow

and be a crop for several years to come.

The planting was done with an 8 foot grain drill pulled

by four horses. The alfalfa seed was placed in a small

hopper, along side the big hopper that held the oats. and

will be seeded at the same time. All went well the first

day in the field. The second day began with another bright

morning, but by noon the sky was gray and cloudy. By the

middle of the after noon it began to snow. With in an hour

there was so much snow on the ground that I had to quit.

I unhitched the team and went home. By nightfall there was

six inches of snow. There was no wind and everything was

covered with a white blanket.

The next morning it was still snowing. The grain drill

that I had been using was so well covered that all I could

see above the snow, was the seat, and the top of the hopper.

There was still no wind, this was not like Western Nebraska.

There was nothing we could do in the field, but now we had a

new problem. Dad was a horse breeder and foals were

arriving. We had to spend all day getting them into dry

quarters. It was necessary to scoop enough snow to get the

herd to feed and water. There was now 3 feet of soft white

snow on the ground, and still snowing.

Monday morning arrived, the third day of the snow. An

emergency telephone call, a series of rings, announced that

there would be no school today. I was feeling good about

everything, because this would be a vacation. It wasn't

long before the phone rang again, this time it was two longs

and two shorts, that was our ring. Dad got up from the

breakfast table to answer. He talked for some time, and from

the tone of his voice I knew that something was not good.

I heard him say, "I can send him over, but I am not sure that

he can get there." HIM meant me, and I didn't want to go

anywhere.

Dad came back to the table and sat down. I was afraid

to start the conversation, so I said nothing. Finally, what

seemed ages to me, he said, "Dawes Forbes is sick and in

bed. He can't get his cattle to feed or water and he wants

you to help him for a few days." I didn't want to go any

where, above all things, I didn't want to go to work for

Dawes Forbes. I got along with him, but he always called

me KID, and I didn't like to be called KID.

|  | | | Page Image | |

It was now the third day of the storm. The sun was

beginning to show thru the clouds. There had been no wind,

and the snow was now 4 feet deep, it was beautiful to see,

a white sea of snow, but almost impossible to go any place.

Dad said, "You had better try to go." I grudgingly went to

the barn to get my saddle horse, Baldy, the horse that I had

been riding to school, and headed for the Dawes Forbes'

ranch. It was only three miles, but I think the longest

three miles I have ever traveled.

Dad suggested that I not go around by the road, and

take a pair of wire cutters with me and cut the fence. Baldy

wasn't pleased with what I was doing, but with some urging

she waded out into the snow. I would follow the fence line

as far as I could. There was no other guide line, and even

then it was hard to see. There had been no wind, only

the tops of the posts appeared above the snow. The white

caps made them look like a line of little soldiers standing

quietly at attention.

It took me nearly two hours to reach my destination.

Baldy couldn't carry me and wade thru the snow. I put the

lariat over the saddle horn, and drove her ahead of me.

What I saw when I got there was very discouraging.

There were both cattle and horses to feed and water. Some

of the cows were calving, and two of them were having

trouble, which was a problem that took a lot of time.

Two days of hard work; The wind did not blow, and

the sun melted the snow, so in a short time we could move

around. When it became time to go home, Dawes Forbes

thanked me, gave me two dollars, and said, "KID, you did a

good job."

|  | | | Page Image | |

PUMPS AND WINDMILLS

The homesteader with a good well on his place, had

another problem to solve, the water had to be raised from

the bottom of the well to ground level. It was always

possible for a person to attach a 3 or 4 gallon pail to a

rope, and let it down in the well, and when the pail hit the

water, give the rope a quick jerk and the pail would flip

over and fill with water, then pull the rope hand over hand

until the pail reached the surface. One person would have

to work all day to water 100 head of cattle.

I have seen many types of inventions that made it easier

to get the water out, than just dropping a bucket in the

water and then hand over hand draw it to the surface. The

first improvement was a single pulley mounted above the

well. This made it possible to get the water to the surface

with out leaning over the well.

The next improvement was a windlass. An A type frame

was set over the well, a long rod placed thru the A frame.

This rod was placed thru a small drum around which the rope

could be wound. A crank on the rod was turned by hand and

would lift the bucket of water. This was a great improvement

over the pulley, but required a lot of time and labor.

The next improvement was the long-handled pump. The

design of the pump was much like those in use today. It was

a cylinder, a piece of pipe, 2 or 3 inches in diameter,

18 inches long, with a plunger in side the cylinder. A rod

then connected it to the pump handle, as you lifted and

lowered the handle you would lift and lower the plunger

inside the cylinder. Three flutter valves were used in the

cylinder, one on each end of the cylinder and one on the

plunger. The valve in the bottom of the cylinder held the

water while it was being forced out thru the top valve.

When the stroke was completed, a cylinder full of water

would be pushed up thru the pipe and out of the pump. A

small (weep) hole was drilled in the pipe, just far enough

from the top of the ground to permit water to drain back

after pumping. This would prevent the pump from freezing in

very cold weather.

The pump could always be worked by hand, but some one

figured that the wind wheel could do the work for them. The

windmill was not new, it had been used for a long time. Man

were home made on the order of a wind-vane, the best ones

were made commercially. We had a SAMPSON on the homestead

in western Nebraska, but there were several other makes. [sic] the

Fairbury, the Aero and others.

|  | | | Page Image | |

The windmill required a lot of attention. The gears

needed to be lubricated, and this would be done by climbing

the tower on which the wheel was mounted, 30 or 50 feet

high. It seemed to me that the wind was always blowing when

I climbed the tower, so I tied the wheel to prevent being

knocked off by a sudden gust of wind. I would cover all the

moving parts with oil and grease, then release the wheel and

hope that I could get out of the way before a gust of wind

would catch the wheel and knock me off the tower.

I have heard of men getting their hands caught in the

gears if there was a sudden burst of wind. We had a friend,

when we were on the ranch in Nebraska, who had fallen from a

20 foot tower, Johnnie Nicholas from Mason City. He fell from

the tower when the wheel turned suddenly, knocking him off,

and he was hospitalized for a long time with a broken

pelvis, arms and ribs.

In recent years many of the windmills in the western

plains were replaced with electric motors. There is often

more cost, but the electricity made it worth while. If

the wind doesn't blow, you can still pump water. A float

switch can be used that will turn the motor off when the

tanks are full. A savings in worn out pumps that were

always in motion if the wind was blowing, made the expense

worth while.

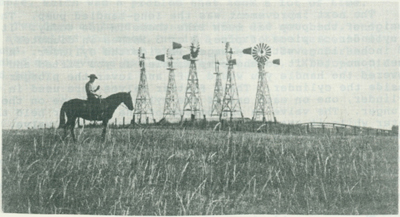

| These windmills were on the Watson ranch north of

Scottsbluff, Nebraska. This type of windmill was used on

ranches in Nebraska. Usually there would be only one

windmill and a stock tank in a location. They would be

placed in a number of positions throughout the range land so

that livestock did not have to go far to water. |

|  | | | Page Image | |

EARLY WINTER

Winter on the Western Plains, for the homesteaders,

was a dreaded time. If snow and cold came in September, it

could be especially hard. The growing season, in Western

Nebraska, could be as short at 90 days. Hay for the horses

and cattle would have been harvested, but grain crops

could still be in the field. Garden crops, such as carrots

potatoes and cabbage, could be caught in an early freeze and

be a catastrophe. These crops meant basic food for the

family. The meat that was most often available was beef

or pork, butchered on the farm. Farm families lived very

well if crops matured early enough to be harvested.

I remember only one year when we got caught with an

early freeze. I think that I was 12 years old, the year