Speculating on the Frontier: Historical Background for John McConihe's experiences in the Nebraska Territory

The adventures of John McConihe in the Nebraska Territory provide a fascinating insight in the life of an early pioneer. Not the typically featured homesteader, McConihe came before the hubbub of the Homestead Act of 1862, when the territory was first developing. Arriving in the Nebraska Territory in 1857, McConihe embarked on the business of speculation during his five year stay.

Meet John McConihe

| | John McConihe, c. 1861 |

John McConihe began his life in 1834 in Troy, New York, born to an old New York family. At sixteen he attended Union College in Schenectady, New York. Following graduation in 1853, McConihe spent a few months studying law with his father before entering the Albany Law School. Upon his graduation in 1855, he returned to Troy to establish his own practice. Soon thereafter he was struck with the desire to go to the "Far West," no doubt enticed by reports of interest and his friend John Newton already in the Nebraska Territory. At 23, McConihe left New York for the rough frontier and promised profits.

Luckily, McConihe had the high spirits and hope needed to survive on the Great Plains. Settling in the Nebraska Territory in the growing town of Omaha, McConihe was interested in speculation on land, corn, freight and other schemes. Besides business ventures, McConihe involved himself in local politics and befriended several notable Nebraskans, including a friendship with J. Sterling Morton. Over the duration of his stay McConihe worked several positions in the territorial government as private secretary to the territorial governors William A. Richardson and Samuel W. Black, and was also appointed Notary Public and Master in Chancery. McConihe had his hand in building several towns; he owned stock in Columbus, lots in Sioux City and Omaha, interests in Nebraska City, and was one of the founders of Beatrice.

As a resident of Omaha, McConihe witnessed the rush of people during the Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1859, survived the financial Panic of 1857 debt free, and awaited the arrival of settlers for his profit.

When the Civil War broke out he joined the First Nebraskan regiment and captained Company G. His tour of duty along the Missouri eventually led him back to his home state and he was transferred to the 169th New York Company and he rose to the rank of Colonel. During his service he was wounded in the shoulder at the Battle of Shiloh. His military career, his life, was cut short on June 1, 1864 at the battle of Cold Harbor when he was shot through the heart as he led a charge.

Notes on McConihe

The collection of letters written by John McConihe to his business partner John Kellogg, detail the operation of their land speculation dealings and other business. McConihe for the most part wrote of finances and current land warrant markets. In his correspondence with J. Sterling Morton, McConihe wrote often of politics and the social scene in Omaha. McConihe also wrote frequently of his health and mood, his high spirits, and some notable events in Omaha or Beatrice. From his letters, it could be gleaned that McConihe was a well connected man who had business deals with the leading men in Omaha, such as the real estate king Byron Reed. He was in the public eye as candidate for mayor and for his involvement in the territorial government.

Gradually, McConihe developed an appreciation for the frontier; like many who settled on the Great Plains the charm of the area was too great to resist. However often he mentioned the "dull" times, he would also describe the beauty of Eastern Nebraska. On August 2, 1857, on one of his many trips back and forth from Omaha and Beatrice, he slept on the open prairie and wrote it was the best night of sleep he ever had.

Often the markets for Land Speculation would slump and he was left lonely and bored. McConihe longed for his family and friends in Troy, but his spirits were never completely broken. He maintained high hopes throughout the duration of his stay in the Nebraska Territory. When bored he entertained himself with social events with local personalities at the Herndon Hotel, had gone to the circus along with (by his count) 1500 people in June 1857, gone sleighing in the winter of 1858, attended local Claims Clubs and the Nebraska Association meetings, and attended on one occasion an Omaha Indian War Dance exhibition. There was always the habit of watching the immigrants pass through. The Gold Rush of 1859 brought a number of interesting characters for McConihe to observe: "A large party came to the Bluffs night before last from Wisconsin en route for the mines. They brought with them a billiard table, which they will take there. There will be gay-times out there next summer, no law but the knife & pistol."

The State of the Nebraska Territory upon McConihe's Arrival

In 1854 President Franklin Pierce signed the Nebraska-Kansas bill, creating the Nebraska-Kansas territory and opening it to a steadily increasing flood of people. In 1854, 2,732 people ventured into the new territory, staying in Eastern Nebraska along the Missouri river. In 1855, 4,494 people had taken residence and in 1856, 10,716 people populated the frontier. The growing population spurred the founding of several towns and aided the growth of old ones; Omaha and Nebraska City grew as gateway cities and Bellevue continued to grow from its beginning as a trade outpost. Numerous towns were platted to accommodate the needs of the new Western population. Healthy real estate business attracted more settlers as lands were snatched up around the cities and into the west, encroaching on the lands of the local Indian tribes.

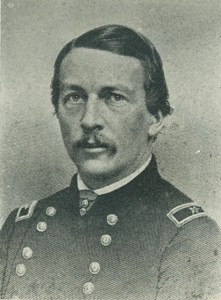

| | Omaha Indian Village on Papillion Creek, c. 1854 |

The lands in Eastern Nebraska through 1854 were still occupied by Indians. The Omaha Indians were living as refugees from their home in the Blackbird Hills in a tipi village on Papio Creek, six miles west of Bellevue. The Otoe-Missouria were living south of the Platte where it joined the Missouri, their tribe in a state of heavy decline and poverty due to disease and alcohol. The Pawnee were driven off their native lands by the Dakota Indians and took residence south of the Platte and to the east of the American settlers with their population in heavy decline due to disease and starvation.

A series of treaties followed in the 1850s that removed the Eastern Nebraska Indians to selected reservations. In 1854 the Otoe-Missourias signed a treaty which removed them to a 162,000 acre reservation in 1855 near the Big Blue River- ten miles from the future location of Beatrice. The Omaha Indians sold their lands in 1854 and received a favorable 302,800 acre reservation on their ancestral lands of the Blackbird Hills which they moved to in 1856. The Pawnee signed a treaty in 1857 that allowed for a 288,000 acre reservation on the Loup River which they moved to in 1859.

Removing the Eastern Nebraska Indians from their native grounds and placing them on reservations did not end the conflicts between the Indians and the white settlers as numerous fights continued. McConihe had several encounters with Indians: he was part of the expedition that confronted the Pawnee in the Pawnee War of 1859, he attended an Indian War dance at the Herndon Hotel-where he regularly spent time-and he chased some Pawnee away from his office. Indian involvement in McConihe's life was minor, but the lands ceded to the government by the Indians were indeed central to his life.

| | City of Omaha, c. 1861 |

When McConihe arrived in Omaha in 1857, he took residence in a newly charted "city." In the spring 1857, real estate was slow and "dull" (a term he frequently used) due to the uncertain opening of the land office, the rush into Kansas, and the large number of people with little to do but wait. Locating on Farnham Street in Omaha, McConihe set up his office and commenced the business of speculation.

After the financial Panic of 1857, Omaha quickly developed into a city. Young John oversaw the building of hotels, offices, churches, homes, stores, and the grading of streets. In 1860 he wrote of the telegraph pole installation, which he was quite excited about, "It looks some like civilization to see the telegraph in our midst. Omaha is destined to come out all right."

Authorized by the United States Congress in 1860, the telegraph line ran from Missouri to San Francisco at the cost of $40,000 per year per ten years. The company Western Union took the contract and by September 5, 1860 the line from St. Joseph to Omaha was open.

Omaha was also the location of the territorial capitol. The first Governor of the Nebraska Territory, Francis Burt, was given the power to designate the capitol. With his early death ten days into his service, Secretary of the Territory Thomas B. Cumming took over briefly as acting Governor and selected Omaha as the site of the legislature in 1854. Immediately that decision was contested and would be challenged for twelve more years until the removal of the capitol to Lincoln.

Founding of Beatrice

Before he arrived in the Nebraska Territory, McConihe was involved with the planning and development of the town of Beatrice, starting immediately his schemes for profit. On the last leg of his journey from Troy to Omaha, McConihe took an old side-wheel steamboat "Hannibal" up the Missouri River, leaving St. Louis on April 3, 1857. Twenty three days into the voyage the boat was temporarily stranded on a sand bar in the Kansas Territory. During the break in travel, thirty five enterprising men of good spirits assembled and formed an association defined by a constitution to remain together and settle as a colony somewhere in the Nebraska Territory. McConihe's motive for joining the Nebraska Association was prompted by profits, but was largely driven by his relationship with John Newton. By entering the Nebraska Association, McConihe hoped to entice Newton into a new business venture with the additional draw for Kellogg to relocate to the Nebraska Territory. However, Newton left the Territory shortly after McConihe's arrival having lost the "nerve" for frontier living and having only just survived a severe fever.

At that first meeting of the Nebraska Association officers were elected with John F Kinney as chair and McConihe as secretary. Beyond electing officials, the meeting included the business of selecting the area of Nebraska to settle in and drafting articles for the association. A committee of five, including McConihe and presided by Kinney, was created to write the articles and present them at the next meeting. The second meeting took place on the following day and the articles were presented and unanimously approved. The third meeting of the Association was held on April 28, 1857. The meeting entailed a census of its members and the creation of the locating committee to explore the territory and select the town site (in accordance with the fifth article). The locating committee split its five members into two groups: one group of two went west and one group of three went southwest into Nemaha County. It was there that they would select the land to form Beatrice.

| | Julia Beatrice Kinney, c. 1860 |

On May 20th 1857, the Nebraska Association met in Omaha where the proposed location of Beatrice was put to a vote. The land between the two tributaries of the Big Blue River was presented as the ideal location and was unanimously accepted to become the future town site. Following acceptance, several more committees were created to handle the development of the town- to designate the location and survey the land, and to find a name for the town. "Beatrice" was the name chosen after John Kinney's oldest daughter, Julia Beatrice Kinney. The fifth meeting of the association was on July 17, 1857 in Beatrice. Most of the members arrived early for the Fourth of July celebration, the first of its kind in the county.

McConihe's property in Beatrice included 45 lots (40 x 50 feet), with 160 acres of timbered land and 160 acres of prairie land. He secured the same for Kellogg.

Increasingly, McConihe focused his attention on Omaha and sought to sell off his major holdings in Beatrice by August 1857. In fact, McConihe secured a surrogate agent (Thad Walker) to act on his and Kellogg's behalf in matters of importance in Beatrice as his interest in Omaha developed.

Business Partners

The bulk of the correspondence between McConihe and Kellogg comprised business accounts. McConihe was careful to assure Kellogg that he was an excellent agent; he often affirmed he would do right by Kellogg and would be careful in all endeavors. For the duration of his stay in Nebraska, McConihe's partnership with John Kellogg worked beneficially for both parties. There were disagreements, but for the most part, McConihe acted with Kellogg's confidence. Two serious disagreements occurred in the life of their partnership; one early row sparked a lengthy debate about whether McConihe was taking Kellogg for a ride. The second was concerned with their surrogate land agent in Beatrice, Thad Walker, and the arguments between Walker and McConihe.

The first disagreement sparked many inflammatory words between Kellogg and McConihe. In September 1857, Kellogg and McConihe grew heated as they argued over the intentions of McConihe's August 31, 1857 letter congratulating Kellogg's election to cashier. In his letter responding to Kellogg's declaration that he wouldn't be visiting Omaha in the fall, McConihe wrote that he thought Kellogg's presence in the territory would be pointless and that Kellogg would be better suited to orchestrating more wealth for himself using his influence and popularity in his newly elected work as cashier.

The following letters further antagonized the men as they detailed the accounts of business and funds thus far. McConihe wrote of putting more money into the business than Kellogg, and that Kellogg's call for repayment was more than he was due for his contribution. No doubt the tension of the financial Panic of 1857 frazzled the nerves of Kellogg and McConihe, providing an impetus for finding fault in the way they were currently conducting business. McConihe dropped the usual salutation of "Friend" and sent Kellogg a report of their current accounts intended to clarify their standings.

The other disagreement was between Thad Walker and McConihe in November 1859. It concerned compensation and the transfer of land warrants. Walker, thought to have been cheated by McConihe in money, accosted McConihe and Kellogg, believing the pair to be in league against him. McConihe, angered for involving Kellogg, in the conflict called Walker crazed, un-businesslike, un-gentlemanly, and dishonest about the compensation for his work on the sales of the land warrants entrusted to him.

The tracking of the land warrants had become confused, and McConihe labored to clean up the mess. McConihe was eager to close their business with Land Warrants. Impatient and distraught he believed he was once again being accused of cheating his business partners. McConihe was able to sort the money and land warrants out and was able to pay the money due to Walker and Kellogg. The business of land warrants was closed out by March 12, 1860.

The Main Draw: Speculation

The business of speculation was a lucrative occupation in the Nebraska Territory. Swarms of calculating men ventured, or sent surrogate agents, to the frontier eager to take advantage of the poorly enforced land laws. Securing land promised great riches in the future when the settlers moved in and bought up available lots.

Land in the new territory was obtained in one of two ways. First, under the Pre-emption Act of September 4, 1841 and second, through soldier's military bounty land warrants. McConihe used both methods but utilized the Pre-emption Act in greater frequency to obtain land.

The Pre-emption Act allowed for the purchase of 160 acres with title available for a payment of $1.25 acre when the land was put up for sale. The Act originally allowed for pre-emption on lands surveyed only, but with the immense numbers of immigration land speculation ran ahead of the surveyors. The federal government recognized the futility in enforcing the survey proviso so the U.S. Congress provided that certain areas, namely the Kansas-Nebraska Territory, could be settled on without survey. The Act also stipulated that the assignment of rights prior to the issue of patent was forbidden in order to prevent speculation and restrict pre-emption to actual settlers. However, nothing restricted a pre-emptor from selling their improvements to another, therefore circumventing the law and allowing for rampant speculation. Military Land Warrants, many held by the Spanish War Veterans, could also be sold by the holder to another, so speculators had several options to obtain land.

Prior to the sale of the public lands by proclamation of the President, lands in the public domain were obtained by a settler going out onto the desired land, surveyed or not, and making improvements on the land. McConihe estimated the costs of improvements in 1857 at three dollars. The settler had twelve months to make proof of compliance with the law and pay $1.25 per acre for the land after it had been surveyed. Pre-emptors were not required to make proof and pay for the land as long as the land was not surveyed, offered by public sale, or offered for sale by proclamation of the President. Pre-emptors claimed the land through "squatter's right." Following the proclamation of sale by the President, the preemptors had four options: one, make proof of settlement and pay the $1.25 per acre before the day of public sale, two, by bidding the highest price at the public auction and paying for the land, three, after the conclusion of the sale by locating and unsold land warrants or pay $1.25 per acre, and four, by buying any unsold lands ten years after the public auction at a reduced price.

The first rush for land came in 1854-1857 and was made up of shrewd businessmen and a few honest settlers. To protect their claims the settlers created claim clubs to act as the law. Functioning with the full support of its members, the club's authority was respected by all the settlers for their mutual benefit. Although established in defiance of federal law, they provided order where there could easily have been chaos and with the sanction of a vast majority of settlers, they served as the most practical and effective local government during the early years of settlement. In fact, the first act of the territorial legislature of Nebraska gave legal authority to the clubs. Working like a bully, if a settler were to disregard the club laws a committee headed by the "sheriff" would visit the "jumper" employing coercive tactics and brute force if necessary to remove the jumper. Numerous claims clubs were erected, the first of which was the Omaha Claims Club in 1854. Most adult males were members of a claims club and there were a number of clubs in the territory. McConihe's involvement in a claims club involved activities that on one occasion entailed stealing muskets. The claims club gradually lost its power and importance with the Government survey of the land in 1856 and the land sales in 1859.

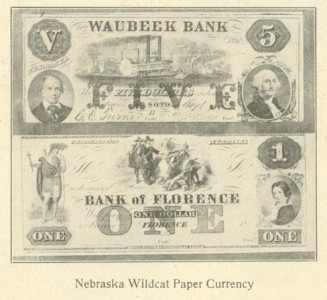

| | Wildcat Bank Notes, c. 1856 |

Leading up to the land sales in 1859 the markets fluctuated greatly. By the end of 1857, the economy was in trouble. The eastern banks failed and finances took a dive. The Panic of 1857 reached Nebraska towards the end of the year. The false sense of prosperity and high optimism fostered the creation of many "Wildcat Banks." The Territorial Legislature had allowed seven banks by charter but as increasing number of banks popped up, the third legislation of the territory repealed the law that made unauthorized banks criminal. This action gave free reign to start up banks and resulted in the banking boom in the spring and summer of 1857. Each bank issued "wildcat" notes of currency. The increasing amount of money in circulation led to inflation. The failure of many banks in the East in late 1857 spread quickly to the territory; every bank in the territory save for two or three were closed. The newly created territorial banks closed just as quickly as they opened. As the banks closed the territory structure failed. Lots devalued, businesses failed, money became nonexistent, scrip became currency and merchandise become the base. The financial depression continued during 1858 and 1859 and the territory's population dropped.

In 1858, in part to create funds for the federal government, President James Buchanan wanted to issue the Proclamation for land sales in the Nebraska Territory. A huge outcry by the settlers followed; the settlers wanted to acquire temporarily free homesteads by putting off the land sales. In addition, postponement would allow the preemptors time to make some money so they were able to pay for their land. The pressure of finding funds for the sales would have driven the settlers into the pockets of speculators and money lenders, and was therefore protested vehemently. McConihe briefly considered the prospect of lending money to settlers, but decided to stay away from that venture due to the uncertainty of repayment. With money short, not many, if any, settlers could pay for the lands they were currently working. McConihe was short on money as well and wrote, "These land sales are my only hope now." Mutual protection associations formed in many of the towns to provide a cover for the settlers who were unable to pay for their lands. Governor Mark W. Izard acted for the Territory and persuaded President Buchanan to postpone the land sales until the summer of 1859, to general relief.

From his arrival in 1857 to March 1860, McConihe engaged in the business of Land Speculation. Acting for his business partner John Kellogg, McConihe bought and sold a collection of over 200 land warrants from the areas of Beatrice, Omaha, Columbus, and Sioux City. During the three year speculation period, McConihe and his agents sold their warrants from $.90 to $.87, the last warrant, an 80 acre claim, was sold for $70.

Bringing the territory slowly out of depression, a saving grace was discovery of gold at Cherry Creek. The influx of "Pikes Peakers" brought large numbers of people through Omaha boosting business and morale. That boost was threatened, however, when many prospectors returned East with no gold prompting great fear and tension in the city. Prevalent was the feeling that the emigrants would trash the city as they returned to their plough shares. The discovery of gold also created the demand for supplies and the freight business, which pulled Omaha out of depression and ultimately made Omaha a city.

With the conclusion of McConihe's involvement in Land Speculation and the onset of gold seekers, he turned to the lucrative freight business. Heavy immigration West from the 1840s on had created an insatiable demand for goods. As the number of settlements increased and the need for military forts to protect them increased, the demand for supplies steadily rose. Omaha developed as an important freighting and emigrant outfitting point due to this healthy market. A good profit could be made, but the freight business was dominated by a few large outfits. A successful operation needed a high number of men, wagons, and animals along with financial backing. Although there were many small freight operations, only the larger outfits could reconcile the costs of business with profit. Although an attractive and lucrative business endeavor, McConihe's attempt was doomed from the start. In early 1860, McConihe proposed the venture figuring the costs to be $2000 in total for mules, wagons, men, and supplies. Many freight businesses operated by delivering a specialty item like apples or delivering a whole range of supplies- what was being shipped depended on the size of the operation. McConihe, with a business partner from Florence, decided on the shipment of molasses, candles, and butter to be shipped from Omaha to Denver and the Pikes Peak mine settlement. August 1860 marked the official start of his freight business and was most likely the high point in his freighting career. What followed was decent profits that trickled down to nothing as the effects of the Civil War caused a removal of military personnel from the forts in the territory. A resulting slow in emigration to the territory occurred as settlers were frightened of Indians; they instead moved further west to California. McConihe was left with a dead business ruined by the Civil War. McConihe cut their losses and sold off the business in May 1861 to Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company (C.O.C. and P.P. Express Co.), the company that began the famous Pony Express in 1860.

Other interests in speculation came in the form of cattle and corn. Corn speculation was a highly profitable business that McConihe talked of entering but missed his chance. Following the financial panic of 1857, many turned to farming to survive and with the spike in agricultural production the agricultural industry took off. Corn became the dominant crop and brought profit to those invested. Likewise, cattle were a lucrative investment that developed a niche in the current markets. Neither opportunity was taken advantage of by McConihe nor his business partners, but plans had been in the works. Several letters were sent to Kellogg asking for funds to take advantage of the wonderful opportunities for profit, but no action resulted.

Despite the uncertainty of success in the speculation business, McConihe stayed out of debt until the early 1860s. This was a proud fact to McConihe; he valued his good standing and was mortified to have gone into debt. When writing of his woes he always asked that his financial troubles were kept confidential. Throughout the duration of his stay in Nebraska, McConihe would often draft on Kellogg for funds, but was confident in his abilities as a land agent to pay Kellogg back and make a profit. It was only in the uncertain financial times brought on by the Civil War that his prospects turned sour.

The Pawnee War of 1859

During the spring and summer of 1859, the area of the Platte Valley-north and south of the Platte River and along the Elkhorn River-was the site of mounting hostilities between the white settlers and the Pawnee Indians. The Pawnee were starving refugees as they were attacked in their villages and chased off their designated lands by the Dakota Indians. On their move to their summer hunting grounds, young Pawnee warriors committed "minor outrages" along the Elkhorn, robbing and destroying homes and public buildings- namely two Post Offices- in the area. "They have stolen horses, cattle, sheep & e and driven off the settlers at various times by threats and then stripped their cabins of everything they could carry away," wrote Secretary of the Territory J. Sterling Morton in a report to President Buchanan on 7 July 1959.

In late June, in response to the depredations, a party of settlers formed and proceeded to surround a small group of Pawnee in a house at the DeWitt settlement and ordered them to surrender. The Pawnee opened fire wounding one man in the shoulder and the settlers returned fire killing four Pawnee. Immediately after the confrontation the settlers sent a courier to Omaha with news and a cry for help.

In Omaha, Governor Black was away at Nebraska City with his family when the news arrived. Secretary Morton approved an expedition led by General Thayer to help the settlers. Black arrived in Omaha on 5 July with a portion of Company K 2nd Dragoons commanded by Lieutenant Beverly Robertson, and quickly organized a small force with several staff officers, including McConihe, to reinforce General Thayer. On 8 July, a force of 200 men consisting of militia and volunteers commenced a four day march west. Commander May Morris at Fort Kearney sent all disposable troops, 70 Dragoons, to Fountenelle to meet Black's forces.

The Pawnee were found ten miles north of the forks of the Elkhorn River. The army prepared a charge, but Chief Peta-Le-Sharu advanced to parley and a

conference followed that resulted in the unconditional surrender of the Pawnee, the surrender of

six of the Pawnee men who committed the acts, and an agreement to pay for damages out of their

government annuity pay. The Omaha Nebraskan reported the

damages at an estimated $15,000. In December 1859, the territorial government signed a petition demanding the settlers affected by the Pawnee receive compensation and to do so, appointed a commissioner, the new agent James Gillis, to examine the merit of the claims presented against the Pawnee. Acknowledgement was made that the settler's prior need of money and destitution at the time of the Pawnee War might have prompted false claims. The Pawnee Indian Agent James Gillis protested the damage pay through the Pawnee's annuity payment and argued that many of the claims had been fabricated. Claims filed against the Pawnee amounted to $20,000 where "some of them just and equitable but a large amount of them of very doubtful character . . ." Gillis wanted to make sure that the scrutiny of claims were just and equitable with judicial treatment of pay to the Pawnee (20 of their horses were stolen) and the white settlers. The matter took several years to clear, but further violence was avoided by the removal of the Indians to a reservation in Nance County.

The stream near the confrontation as well as the nearby town was named Battle Creek to commemorate the events. Accounts of the brief Pawnee War, or Pawnee Chase, regarded it as a glorious campaign. McConihe had little to say about the "Chase" merely remarking in passing, "All well, whipt the Indians, traveled 400 miles and had a hard time."

Politics in the New Frontier

To supplement the income gained from Land Speculation, McConihe got a job as the private secretary to the territorial governors. Governor Richardson hired McConihe as interim secretary in October 1858 and was paid $50 per month. In late November, early December, McConihe was appointed Notary Public by Richardson. McConihe stayed on as private secretary through the end of Richardson's term as it was a source of good money and good connection for the young lawyer. McConihe hoped to stay on as private secretary for Governor Black and fortunately was requested to continue for a trial period. McConihe secured the job in May 1859 and the pay increased to $60 per month. McConihe lost the position when Alvin Saunders was elected and he brought in his own man, a Republican from East Iowa.

In 1860 McConihe was encouraged to run for mayor of Omaha and did so, but was defeated owing to his association with Governor Black. Black had gained disfavor by his veto of an anti-slavery bill that had come before the legislature. Black's motivation was to keep the territory out of the slavery debate and was lambasted for his decision. McConihe resigned not to run for office again until he was finished with his job as private secretary to the governor, which he wrote would be as long as he could manage.

Friend of J. Sterling Morton

Through his job, McConihe came into contact with J. Sterling Morton. The two men bonded over their similar backgrounds; both were from well to do families, were educated, and were Democrats. McConihe wrote many letters to Morton beginning in 1859, visited his home, and lent Morton money and his support when Morton made a bid for Congress. The correspondence between Morton and McConihe detailed the political scene; William Daily versus General Experience Estabrook, who "must be elected or we are all gone up politically," in the election of 1859 for Congress, and Morton's election campaign were common subjects. They also exchanged letters concerning the finances of the territory and McConihe often wrote of news in Omaha.

It is clear that McConihe admired J. Sterling Morton and his wife Caroline Morton. McConihe often asked after Caroline and the children always wishing them well. McConihe often sent for Morton, requesting his soothing presence and wrote how he missed Morton's pleasant face in Omaha. He also favored Caroline, sending her the best fan and soap that he could attain. McConihe's admiration also extended to the Morton home in Nebraska City. A visit and subsequent return to the dust of Omaha and the now shabby Herndon Hotel left him envious of farm living, he remarked, "I believe I would move on a farm to-morrow, if! if! I was anything but a poor bachelor."

A special request was asked of Caroline Morton; McConihe asked her on several occasions to assist him in finding a wife. Once, McConihe specifically asked her to temper the father of a woman he was interested in. His frustrations with the father prompted McConihe to reflect on the subject of love and marriage:

McConihe's troubles with females didn't end with the obstinate parent (McConihe's early remarks to Kellogg in January 1860 didn't hold long: "The "females" trouble my heart but little and you may rest assured there is no "lovely Angel" that detains me in Nebraska. Nothing more than business." Rumors began circulating of his engagement to an unnamed woman so he wrote a letter to Morton informing him the rumors were false and that Mrs. Morton should not credit the "yarns" or further circulate them.

During the Civil War, relations between McConihe and Morton deteriorated. McConihe sent several

letters to Morton that went unanswered, leaving McConihe to bitterly retort, "I will not bore you

with a letter as you have several of mine unanswered . . ." According to the letters, Morton never repaid McConihe the money he owed him ($178.33) or repaid Kellogg the draft borrowed ($130). Morton's inattention to these business matters perplexed McConihe who had observed that he was always prompt when it came to finances. McConihe was friendly to Morton throughout their dealings, but he grew impatient with no response from him. McConihe wrote letters to Morton's father in Michigan in an attempt to contact him. Morton did reply in August 1862, but didn't include repayment nor did he smooth the irritation over his lack of correspondence.

The Civil War

Although removed from the frenzied turmoil in the east, the Nebraska Territory felt the effects of the Civil War. Markets plummeted and migration trickled to Nebraska as pioneers continued west to California in what McConihe saw as the largest migration since 1849; the move away from the Great Plains was propelled by the fear of Indians in the territory and the lack of protection offered due to emptied military forts. McConihe first thought the panic of war in the East wouldn't be felt in Nebraska and would instead boost the markets and migration. Unfortunately, McConihe was wrong. The Civil War put an end to McConihe's freight business, and after his loss of job as private secretary, McConihe had limited options to provide funds and to occupy himself during the onset of war. In his letters, McConihe wrote of his plans if "disunion" befell the country. In a January 1861 letter to Kellogg, he decided he'd leave the region and go back East, however, "Still this may be a good place to make money, only I fear, life will be insecure on the Frontier. Between Indians, Robbers, and Thieves, Assassins and Pimps, a man with a few spare dollars might stand a poor chance of "lingering here below."

As tensions mounted prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, McConihe wrote many letters discussing the matter of disunion: "I do not know, I cannot see, what is to be the fate of our Country. Everything looks gloomy and dark to me in the future. Are we to subjugate the South and can it be done? If it is done, what have we accomplished? Will our Republican form of Government remain and how long must war continue? All these and many other questions bring gloomy forebodings to my mind."

McConihe believed that the war could have been avoided, but given the "fearful realities" he sided with the Northern Union and patriotically declared to ". . . bear aloft proudly the ensign of our Union, and never let the Stars and Stripes be trailed in the dust. Perish all first." He thought that the East was frenzied and hungered for fighting as they were caught up in the excitement of war.

The bloodthirsty nature of the news and current opinion of the population repelled him; although willing to fight to sustain the federal government McConihe didn't want to enlist in barbarous warfare and desired to fight in a Christian manner. Removed from the battles in the East, McConihe wrote that Omaha was safe and that there would be no fighting save for the lynch law in force by Omaha citizens.

McConihe ended up staying in the Nebraska Territory. Pressured by his inability to pay his debts and the current depression, McConihe joined the First Nebraska Regiment at the pay of Captain in July 1861. He received his orders to leave for Fort Leavenworth at the end of July 1861. Occupied with his new "business" of warfare, McConihe wrote rarely during his service time to Kellogg. One longer letter came with a brief rest from heavy marching (a fact he lamented: "There is no honor in marching, bring on the battle!" During the course of his service he managed to return to Troy and made trips to Washington D.C. and was in Cincinnati, where he had surgery to remove shattered bones from his arm on June 22, 1862. His arm was slow to heal, writing on July 15, 1862 of the pain lamenting that his arm would never recover full function.

McConihe did plan on returning to the Nebraska Territory following his service. He looked fondly on his brief time spent on the frontier and looked hopefully towards the future, "Oh; how I would like to go back and live over those pleasant days in Nebraska. But that cannot be. They are past and the old friends are separated scattered far & near. But I hope there is much pleasense [sic] in life yet for me & know there must be for you. So the clouds will clear away and there will be sunshine again." Unfortunately, McConihe's death in battle cut short the experiences this pioneer would have had in Nebraska.

Bibliography

Dobbs, Hugh J. History of Gage County, Nebraska. Lincoln: Western Publishing and Engraving Company, 1918.

Olson, James C., and Ronald C. Naugle. History of Nebraska. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Olson, James C.. J. Sterling Morton. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1942.

Savage, James W., and John T. Bell. History of the City of Omaha Nebraska and South Omaha. New York: Munsell & Company, 1894.

Sheldon, Addison Erwin. Land Systems and Land Policies in Nebraska. Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1936.

Sheldon, Addison Erwin. Nebraska: The Land and the People. Vol. 1. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1931.

Sorenson, Alfred Rasmus. History of Omaha from the Pioneer Days to the Present Time. Omaha: Gibson, Miller & Richardson, printers, 1889.

Wishart, David J. An Unspeakable Sadness: The Dispossession of the Nebraska Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

1. ()

2. ()

3. Sheldon, Addison Erwin, Land Systems and Land Policies in Nebraska (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1936), 35.()

4. Wishar, David J., An Unspeakable Sadness: The Dispossession of the Nebraska Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 86-87.()

5. Ibid., 88-89.()

6. Ibid., 90-94.()

7. Ibid., 102.()

8. Ibid.()

9. Ibid.()

10. Ibid.()

11. ()

12. ()

13. Olson, James C., History of Nebraska (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972), 112-113.()

14. Sorenson, Alfred, History of the City Omaha from the Pioneer Days to the Present Time (Omaha: Gibson, Miller & Richardson, 1889), 50.()

15. Ibid., 53.()

16. Dobbs, Hugh J., History of Gage County, Nebraska (Lincoln: Western Publishing and Engraving Company, 1918) 117.()

17. Ibid.()

18. ()

19. Ibid.()

20. Dobbs, History of Gage County, 117.()

21. Ibid., 117-118.()

22. ()

23. Dobbs, History of Gage County, 120.()

24. Ibid.()

25. ()

26. ()

27. ()

28. Sheldon, Land Systems and Land Policies, 28.()

29. Olson, History of Nebraska, 88.()

30. Ibid.()

31. Sheldon, Land Systems and Land Policies, 25.()

32. ()

33. Sheldon, Land Systems and Land Policies, 28.()

34. Ibid.()

35. Ibid.()

36. Ibid., 33.()

37. ()

38. Sheldon, Land Systems and Land Policies, 34-35.()

39. Sorenson, History of the City Omaha, 149-161.()

40. Olson, History of Nebraska, 90.()

41. ()

42. ()

43. Olson, History of Nebraska, 90.()

44. ()

45. Ibid.()

46. ()

47. ()

48. Olson, History of Nebraska, 94.()

49. Morton, J. Sterling, Letter to President James Buchanan, 7 July 1859.()

50. Savage, James W. and John T. Bell, History of the City of Omaha Nebraska and South Omaha (New York: Munsell & Company, 1894), 151.()

51. Morton, Letter to President Buchanan, 7 July 1859.()

52. Sheldon, Addison Erwin, Nebraska: The Land and the People, Vol. 1 (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1931.), 292-293.()

53. Morton, Letter to President Buchanan, 7 July 1859.()

54. Ibid.()

55. Sheldon, Nebraska: The Land and the People, 292-293.()

56. Morton, Letter to President Buchanan, 7 July 1859.()

57. Wilson, P.F., Letter to President James Buchanan, 7 July 1859.()

58. Sheldon, Nebraska: The Land and the People, 292-293.()

59. Ibid.()

60. "History of the Pawnee War," Omaha Nebraskan, 9 July 1859, Vol. 5 No. 25, p 1.()

61. Nebraska Territorial Legislature, Committee Memorial and Resolution, December 1859.()

62. Gillis, James, Letter to A.B. Greenwood, 6 February 1860.()

63. Ibid.()

64. Ibid.()

65. Wishart, An Unspeakable Sadness, 121.()

66. ()

67. ()

68. "Vote for John McConihe," The Daily Nebraskan, 4 March 1860, Vol.6 No.2, p 2.()

69. ()

70. ()

71. ()

72. ()

73. Ibid.()

74. Ibid.()

75. ()

76. ()

77. ()

78. ()

79. ()

80. Ibid.()

81. ()

82. Ibid.()

83. ()

84. ()

|